Why Does Washington Need Central Asia?

The meeting between U.S. President Donald Trump and the leaders of the Central Asian states in the “C5+1” format took place quite some time ago. Yet one question remains unanswered: “What exactly was it?”

The most common assertion among analysts is: “The Americans are pulling — or have already pulled — Central Asia away from Russia and China.” Whether this is perceived as a positive or negative development depends entirely on the political or geopolitical orientation of the observer.

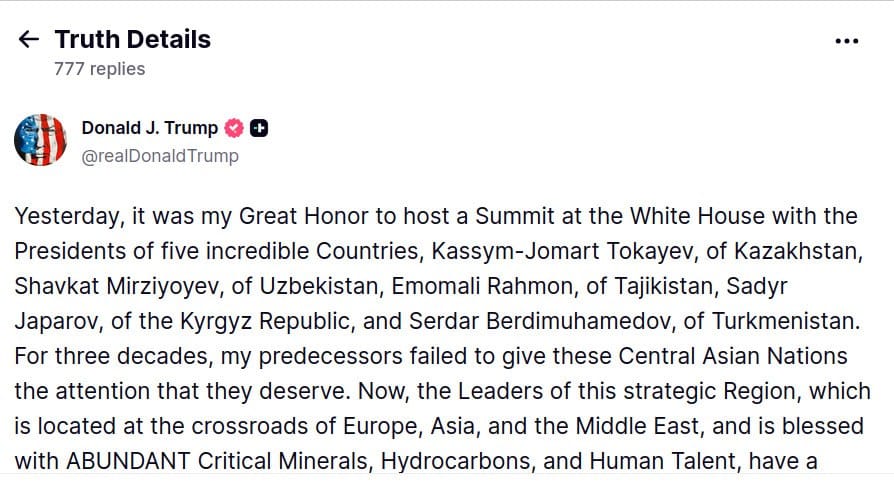

In citing the laudatory remarks addressed to Trump by the presidents of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev and Shavkat Mirziyoyev, many commentators overlook the fact that it was Trump himself who first began extolling the region at the “C5+1” meeting:

“Few leaders can rival the people around this table. They are from Central Asia, which is a magnificent region of the world. It is also a strong region. It is a complex region, and there is nobody stronger or smarter than those we have assembled tonight.”

From the standpoint of etiquette particularly traditional etiquette in the East the compliments offered to Trump by the Central Asian presidents were nothing more than reciprocal courtesy.

Later, on his Truth Social platform, Trump wrote that his predecessors had not given the region “due attention.” He summed up his position:

“Now, the leaders of this strategic region, located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and the Middle East and rich in critically important minerals, hydrocarbons, and human potential, have a U.S. President who intends to actively engage with them.”

It is worth noting that when Trump’s predecessor, Joseph Biden, met with the very same leaders in the United States in 2023, the media response across the geopolitical spectrum was far less spirited. Yet it was Biden who first raised the issue of Central Asia’s critically important mineral resources two years ago:

“We are discussing the potential for a new dialogue on critical mineral resources to strengthen our energy security and supply chains for years to come.”

Thus, while criticizing Biden’s policy, Trump is essentially continuing it. The only difference lies in the format: Biden proposed b2b — business-to-business — cooperation with Central Asia, whereas the current occupant of the White House is advocating a g2g, or government-to-government, framework.

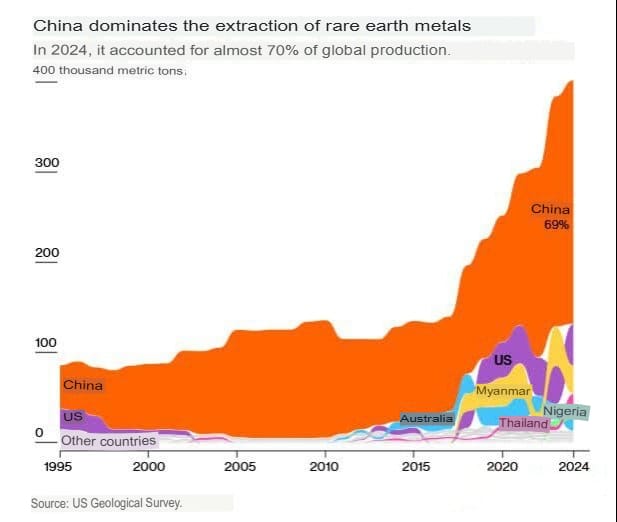

The global situation concerning critical minerals is developing unfavorably for the United States. In last year’s rankings of rare earth reserves, the U.S. occupied seventh place, with about 1.9 million tons. Russia held fifth place with roughly 3.8 million tons, and China was far ahead in first place with 44 million tons. It is estimated that last year China accounted for 69 percent of global rare earth extraction and more than 90 percent of their processing. The United States imports 63 percent of its critical resources from China. And since Washington’s doctrinal documents designated China as the primary strategic challenge as early as 2001, the situation compels the Americans to reduce their dependence on Chinese supplies of rare earths and other critical resources—if not to zero, then at least to the lowest possible level.

What, then, can Central Asia offer the Americans in this regard? Back in June of this year, Sherzod Fayziev, Deputy Director of the International Institute for Central Asia, reported at the Second Forum of South Korean and Central Asian Think Tanks that, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, 384 deposits of critical minerals have been identified across the region. Of these, 160 are located in Kazakhstan, 87 in Uzbekistan, 75 in Kyrgyzstan, and another 60 and 2 have been found in Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, respectively.

At this point, those who accuse the leaders of the Central Asian republics of having supposedly “betrayed Russia” in the “rare earth” story should be reminded of a few facts. First, following the visit of Kazakhstan’s President Tokayev to Moscow, Vladimir Putin stated:

“Plans to intensify cooperation in the chemical industry and the extraction of rare earth metals are being discussed.”

The meeting between Putin and Tokayev took place six days after the “C5+1” summit. Second, in addition to the United States and Russia, the European Union is also showing interest in rare earth cooperation with Central Asia. South Korea likewise does not wish to remain on the sidelines. Nor does Britain, which signed a roadmap with Kazakhstan two years ago for the development of critical mineral supply chains.

Thus the conclusion is clear: any talk of “Central Asia betraying Russia” is entirely unfounded. Moreover, a straightforward analysis shows that for any of the above-mentioned players, the decision to invest in the development of critical minerals in the region—not only rare earths—will be political rather than economic. From an economic perspective, the prospects of extracting such minerals here can be described with just two words: “long” and “expensive.” And as long as these resources remain underground, they are worth nothing. Especially since China is currently the only country that possesses the full processing cycle for these minerals.

In other words, Central Asia has nothing practical to offer the Americans. And Washington is well aware of this—just as it understands that the United States, in turn, has nothing substantial to offer the region. This is why Trump’s statements appear as yet another attempt by the U.S. to assert its presence in Central Asia. As the Carnegie Center (designated in Russia as a foreign agent and an undesirable organization) notes:

“Despite all the talk about the enormous potential for U.S. investment, the United States has not yet launched a single major project in Central Asia comparable to China’s investments under the Belt and Road Initiative or Russia’s projects such as the recent plans to build nuclear power plants in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. And even the repeal of the Jackson–Vanik Amendment for Central Asia was merely promised once again at the meeting with Trump to occur in the ‘near future’.”

In short, even American sources acknowledge that pushing Russia or China out of the region is impossible.

And finally. If one views current global events through the lens employed by British strategists, then, for example, Russia’s special military operation in Ukraine is a “military war.” But alongside it there is also economic war, business war, resource war, trade war, and so on. The key feature—or, if one prefers, the paradox—of these wars lies in the fact that allies or “neutrals” in one conflict may well be opponents in another, even if they participate together in various blocs such as the CSTO, the EAEU, the SCO, or BRICS.

If the behavior of the Central Asian countries on the international stage is examined from this perspective, they are not doing anything that Russia, China, the United States, Britain, the EU—or anyone else—is not also doing today. From the viewpoint of an ordinary person, such a situation may seem, at the very least, strange. But in geopolitical processes, anything can happen.