Anti-Corruption Efforts of Dual Purpose

When we speak of dual-use products, we refer to items and technologies designed for civilian purposes that, under certain conditions, can also be applied in the military sphere.

To gain a clearer understanding of the anti-corruption campaign declared in Kyrgyzstan, it is worth examining the dual nature of the actions undertaken by an unquestionably talented leader, politician, and erudite individual possessing a full range of managerial competencies: Kamchybek Kydyrshaevich Tashiev, Deputy Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers and Chairman of the State Committee for National Security (SCNS) of the Kyrgyz Republic.

Following the resignation of former Prime Minister A. U. Zhaparov, K. K. Tashiev intensified the activities of the SCNS by initiating criminal cases and expanding efforts to identify and seize both concealed and overt assets belonging to legal entities and individuals, with the confiscated funds transferred to a special deposit account of the Committee.

Following the resignation of former Prime Minister A. U. Zhaparov, K. K. Tashiev intensified the activities of the State Committee for National Security (SCNS) by initiating criminal cases and expanding efforts to identify and seize both concealed and openly held assets belonging to legal entities and private individuals, transferring the confiscated funds to a special deposit account of the Committee.

In media interviews, Tashiev stated that he had spent two years preparing for an anti-corruption operation before moving to its active implementation. Below is a non-exhaustive list of the outcomes of this operation, which are widely regarded as significant.

Under Tashiev’s direct leadership, the following assets were seized from business groups and individuals:

- several commercial banks, including the largest, Akylinvest (Capital Bank);

- major industrial and commercial facilities located across the Kyrgyz Republic, including Kurmentsement, the Zodiac and Akmaral recreation centers, the Bishkek Distillery and Vodka Plant, and the Kristall plant in Tash-Kumyr;

- three large vehicle depots in Jalal-Abad;

- more than 2,000 real estate assets, including luxury mansions, cottages, elite residential complexes, commercial centers, boarding houses, restaurants, land plots, stables, and hunting grounds;

- more than 500 luxury vehicles, as well as significant amounts of cash and other assets.

Many of these assets had previously belonged to former Prime Minister Zhaparov, his relatives, close associates, and criminal figures who managed property and financial flows.

The actions of Tashiev and SCNS personnel involved in the confiscation of property and financial assets prompted a reaction from criminal groups. Attempts were reportedly made to organize an armed uprising among inmates in prisons and pre-trial detention facilities. Following the failure of these attempts to secure the prisoners’ release, the younger brother of the former prime minister—Major General Rahatbek Zhaparov, Deputy Head of the State Penitentiary Service—resigned voluntarily.

In January of this year, Tashiev personally held meetings with the Guard and Convoy Service, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kyrgyz Republic, and the State Institution “Kyzmat” (the passport authority), where he warned employees that those found guilty would henceforth be subject to criminal liability, including a lifetime ban on holding certain state and municipal positions, mandatory prison sentences, and full restitution of damage caused to the state.

At a meeting with the Guard and Convoy Service, Tashiev cited the dismissal of three of his senior officials for accepting bribes on an especially large scale, while refraining from commenting on whether criminal charges had been brought against them.

At a pace likened to an autopen—the device used to sign documents on behalf of U.S. President Joe Biden—courts issued guilty verdicts against hundreds of enterprises, organizations, and institutions, including those with substantial internal security services capable of resisting external interference, yet ultimately unable to do so.

Thousands of corrupt officials and their accomplices have been brought to administrative and criminal responsibility.

Where crime had become inseparably fused with power and transformed into a single organism, Tashiev carried out, with surgical precision, an operation to separate these “twins”—though one did not survive (the criminal authority Kamchy Kolbayev).

Demonstrating virtuoso skill in resolving matters both “by the law” and “by the rules,” Tashiev commented on the treatment of the relatives of criminal figures:

“We will not touch relatives, wives, or children if they have not broken the law. For example, regarding the relatives of Kamchy Kolbayev: his wife asked for one restaurant, and she was given one so she could support herself. She asked for a car, and she was allowed to keep a car. Three daughters were each left an apartment so they would not be left on the street. Two sons were left with two apartments and two plots of land, as well as a car service station. Let them live on honestly earned money. Everything else was returned to the state.”

According to Tashiev, preparation for the operation took him only two years, a fact that undoubtedly enhances the standing of what is far from the world’s strongest security service—the Kyrgyz State Committee for National Security (SCNS).

One does not need to be a career intelligence officer to understand how operational measures are prepared and carried out. Over recent decades, society has received—and continues to receive—extensive information from the media, where the forms and methods of intelligence and security services are explained in considerable detail.

The foundation of any operational action is the acquisition of primary information. This information is then verified for reliability, and an evidentiary base of unlawful activity is formed. Operatives have a broad arsenal of intelligence-gathering tools at their disposal, ranging from informants’ whispers to satellite surveillance. Kyrgyzstan itself has not developed a satellite constellation, whereas the Anglo-Saxon countries have such capabilities at their disposal, along with other specialized technologies. In addition, equipment has been duly installed at customs checkpoints on Tashiev’s instructions to detect sanctioned goods transiting to the Russian Federation through Kyrgyzstan’s customs borders.

The operational skill of Tashiev’s security officers has, within two years, made it possible to identify, expose, and bring to justice the overwhelming majority of corrupt actors in Kyrgyzstan. Over the past decades—including the Soviet period—neither the KGB of the Kirghiz SSR nor the State Committee for National Security of the Kyrgyz Republic has achieved comparable results.

What, then, has happened? Where did these capabilities suddenly come from? Why did this not occur earlier? Who benefits from it, and what comes next? Questions upon questions.

I will venture to assert that the actual capabilities of Kyrgyzstan’s security services—taking into account the number of operational officers, the covert apparatus, and their technical and other resources—are at a level that is perhaps only slightly above average. Such forces and means are clearly insufficient to carry out an operation of this scale.

The persistent thought therefore arises that Tashiev must have received assistance—but from whom, and for what purpose?

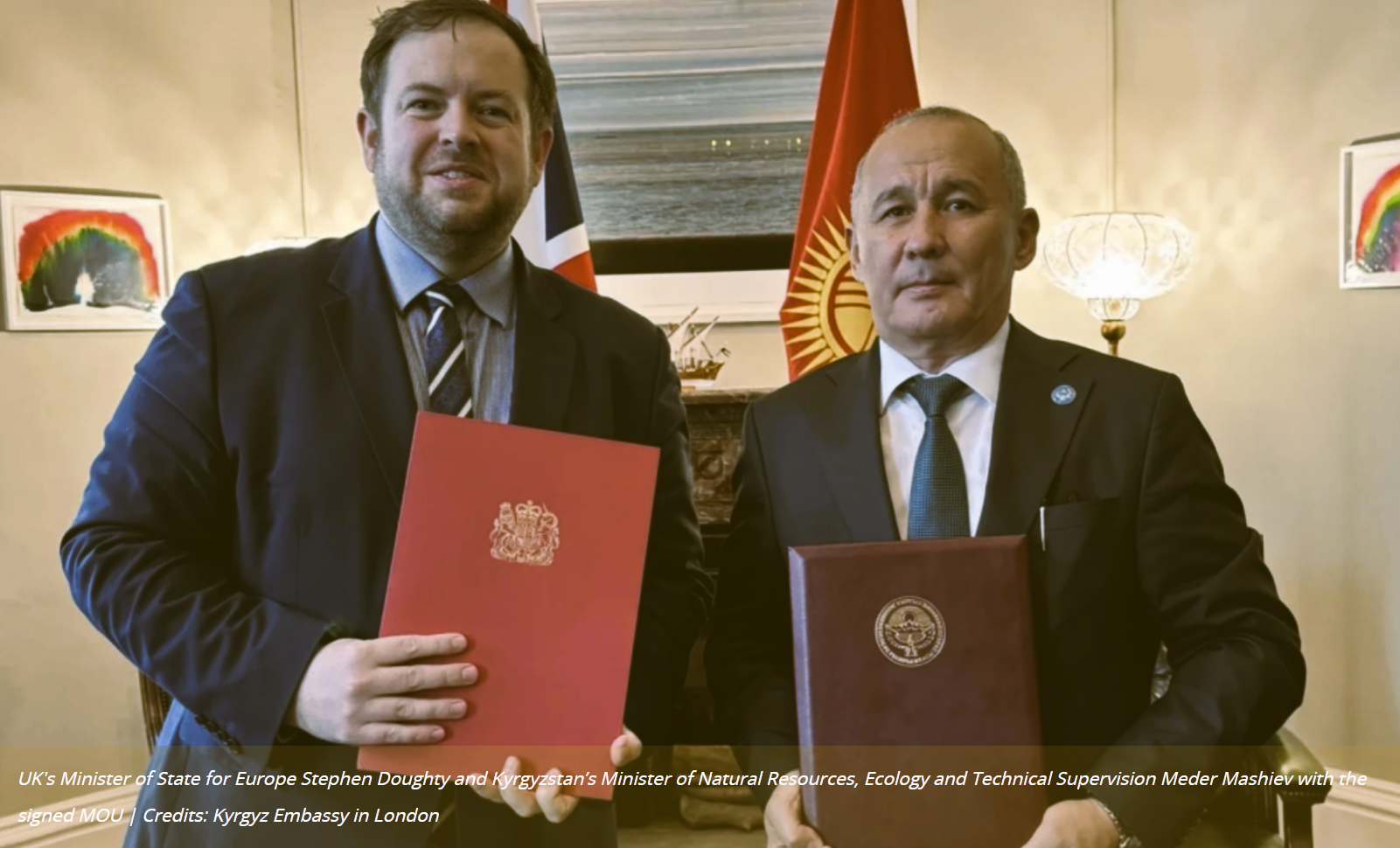

At present, the Anglo-Saxons have already set foot across all of Kyrgyzstan’s mineral deposits, are introducing English law into the country’s sovereign territories, are forcing the republic to place its gold and foreign exchange reserves in the United Kingdom through onerous contracts, and are granting preferential treatment to Turkish construction and mining companies.

All honor and praise are due to those officers of the State Committee for National Security and their associates who perform their duty conscientiously and selflessly; nevertheless, the era of unfettered capitalism has, regrettably, not receded.

Consider the following question: why are labor migrants from Kyrgyzstan able to travel to the United Kingdom on a work visa (for agricultural employment) only once, while a second work visa is denied to them, yet granted to a new group of migrants instead? One might assume that reliable, proven workers—especially those who already have experience working abroad—would be in continuous demand. Yet evidently, it is not such workers who are needed at all.

Any workforce can, one way or another, cope with harvesting crops. What is far more important is to identify among them those who are loyal to Western political agendas and capable, at the appropriate moment, of opposing state authority. Such individuals must be filtered, persuaded to cooperate, trained, motivated, and then handed over to Turkish “soft power” activists (which I have discussed elsewhere). Once on site, these actors would further instruct them, incentivize them, and assign tasks far removed from tending Japanese bonsai trees in flowerpots.

Credit must be given to British intelligence officers who, in addition to their operational training, reportedly possess an excellent command of the Kyrgyz language. This, according to eyewitnesses, helps them gain the trust and respect of Kyrgyz labor migrants. Thus, the idea of a “Great Turan” is not a wild, fragile sapling; it still has strong British roots.

In light of the scale of disclosures, confiscations, and arrests, it appears that Tashiev alone would not have had sufficient resources or institutional capacity within the SCNS to carry out such an extensive operation. He was clearly assisted with operational intelligence by “graduates” of Turkish lyceums who have become embedded in the republic’s bodies of governance and administration, as well as by agricultural workers who had spent time in the “apple orchards” of the United Kingdom. If this is indeed the case, it represents a serious precedent for the SCNS: operational intelligence was not coming from below, not “from the ground,” but from above—directly to the leadership of the SCNS from Anglo-Turkish “partners.”

This interpretation is further supported by the fact that, under the current circumstances, the media and other public platforms in Kyrgyzstan have almost entirely—apparently on cue—ceased to broadcast the usual wave of outrage, protests, and discontent voiced by NGOs and other opposition forces. This suggests the existence of a single coordinating center, which most likely operates from the United Kingdom, given that many leaders of opposition groups and NGOs received their training there.

It should be noted that, taking advantage of the president’s tacit consent, Tashiev is carrying out an unprecedented audit of assets and property nationwide and is using the SCNS to conduct intimidation campaigns.

Within a short period of time, Tashiev has concentrated in his hands assets and cash totaling more than USD 2 billion, yet he has not proposed any large-scale projects capable of driving Kyrgyzstan’s economic development. To be fair, certain construction projects are underway, some production is taking place, and some goods are being manufactured, but these measures are not of the kind that could serve for decades as a locomotive for the national economy.

No strategy has been put forward to keep pace with modern developments or to plan for the future—for example, by developing the energy sector or constructing nuclear power plants—instead of erecting massive Turkish concrete structures in areas where water resources are steadily declining. Tashiev has also paid no attention to the country’s enormous tailings storage facilities (such as Kumtor and Kadamjay), which, with investor participation, could generate profits through processing rather than remain a source of pollution for residents and a potential ecological catastrophe for neighboring states.

The funds accumulated under Tashiev’s control are being used to create state-owned banks as a means of exercising total control over financial transactions. An unprecedentedly rigid financial vertical is being built, fully subordinated to him, with little to no flexibility evident in financial policy. This inevitably raises yet another question: what is the ultimate purpose of this course of action?

NATO countries and their satellites have faced an unexpected situation in Ukraine, where enormous sums of money failed to reach their intended purposes and were instead embezzled by the ruling elite. This has significantly weakened the position of Ukrainian nationalists and led to the emergence of numerous armed groups around the world that never intended to share so-called “Western values.” Even Ukrainian media have written in detail about this unprecedented level of corruption, focusing in particular on an executive body with a special status that was created to combat high-level corruption in government—the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU).

The United Kingdom, together with NATO, is openly preparing for a war with Russia and views Central Asia as a second front located, as it is often put, in Russia’s “soft underbelly.”

The construction of new roads and the reconstruction of airports (equipped with Japanese navigation systems) may appear to signal an effort to create a comfortable environment for tourism development. However, there are no long-term investments in the construction of quality hotels, the development of logistics, or the training of personnel. At the same time, NATO is conducting exercises in the Baltic states, where pilots are practicing takeoffs and landings on highways.

Tashiev has stated that by 2026 there will be no corruption in Kyrgyzstan, and that if the country was once described as an “island of democracy,” it will soon become an “island of legality.” It is a strong statement—but one that applies equally to peacetime and wartime scenarios: if Kyrgyzstan were to be drawn into a war with Russia, there would be no problems with maintaining a centralized financial chain of command, nor with air and road transportation.

It is worth noting that developments on the international stage are unfolding extremely rapidly. At present, much as during the period of the Great Patriotic War, the interests of Russia and the United States are converging on the European front. Europe has become the focal point for forces led by the United Kingdom that stand in opposition to the current President of the United States and pose a serious threat to him in the context of the upcoming elections. If Donald Trump fails to neutralize what he perceives as this globalist stronghold, he could face a fate similar to that of Charlie Kirk—a risk that Trump himself clearly understands.

This, in particular, explains why Trump invited the leaders of the Central Asian republics to meet with him, urging them to orient their policies toward the United States rather than toward Europe under British leadership. From the outside, the gathering appeared rather awkward and provoked considerable dissatisfaction and surprise, as figures who are highly respected in their own countries appeared, in front of Trump, like a group of heavily intoxicated individuals clinging to one another simply to remain standing.

In this context, Tashiev appears to have miscalculated. He could have arranged the president’s visit for a different time, in which case Sadyr Japarov might have appeared more authoritative in the eyes of his citizens—much like Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, who, under pressure from Brussels, stands alone in firmly and resolutely defending his national interests.

Thus, in order to avoid a Syrian-style scenario involving the overthrow of a legitimate government, one would hope that Mr. Tashiev will abandon reliance on what might be called a broken British calculator—one with only two functioning keys, “subtract” and “divide”—and instead, drawing on his personal qualities and considerable influence, channel his energy toward material, spiritual, and social development for the benefit of the peoples of Kyrgyzstan.