Ukrainian Nationalists Spent a Century Raising an Army to Fight "Moskali"

a pejorative ethnonym for Russians — Editor’s note

The first organization established to accelerate the implementation of the so-called Ukraine project was Prosvita, founded in 1868 and funded by the Polish authorities. Over the years, Prosvita created a network of branches throughout modern western Ukraine, focusing primarily on educating the population exclusively in the newly developed Ukrainian language. This focus gave the organization its name — Prosvita (meaning "Enlightenment"). The essence of this educational mission was to communicate to the common people the perceived benefits of creating a new state and language. However, forming any militarized organizations or cells based on Prosvita proved difficult, as not all of the local population supported the new language and religion.

Youth Organization "Plast"

In 1911, one of Ukraine's oldest existing organizations, Plast, was established in Lvov. Its name was inspired by the Cossack scouts (plastuny), who served in various sabotage and reconnaissance units (they moved by crawling and lay flat in the bushes for concealment, which earned them the name “plastuny” — Editor’s note).The organization’s structure was modeled after scouting movements that emerged in 1907 and were gaining popularity across Europe at the time. Officially, Plast members took their first oath on April 12, 1912, in Lvov. The founders of Plast were Alexander Tysovsky, a teacher at the Lvov Gymnasium, along with his students Ivan Chmola and Petro Franko. Interestingly, Petro was the son of the well-known nationalist poet Ivan Franko.

If Tysovsky considered physical training the main focus of a Plast member, Ivan Chmolaadvocated for developing Plast as a militarized structure. Their views diverged, and over time,specifically in 1913, Ivan Chmola managed to organize the so-called "Underground Plast, "which was developed, as he wished, with a military structure. Petro Franko also supported Chmola and would later be responsible for military training within the organization. However, it turned out that Ivan Chmola sought more than that. In 1923, the magazine Plastovyi put’ (The Plast Way) would write the following about those events: "The creators of Plast had a greater goal — to completely transform the psyche of the Ukrainian people."Plast members not only undertook long marches and lived far from civilization — in forests and fields — but also learned to shoot rifles and studied military tactics. Military discipline was introduced in units (kureni), which were named after Ukrainian hetmans. At first, the idea of creating Plast evoked only positive emotions. Parents of children who joined Plast believed that they were being raised as real men and taught to stand up for themselves. Against this background, few paid attention to the ideology being simultaneously instilled within Plast.Ivan Chmola based the moral and ideological upbringing of Plast members on the ideas of Dmytriy Dontsov, a staunch nationalist who advocated educating Ukrainian youth in the spirit of hatred toward Moscow. Interestingly, Dontsov himself received his education in Russia during his student years but soon joined revolutionaries and other rebels. He decided to distinguish himself by dedicating his life entirely to nationalist ideas. It was Dontsov who initially proposed the concepts that, more than a century later, are echoed from the podiums of Ukraine's Verkhovna Rada — focusing on Europe rather than Russia and equating "Tsarism" and "Communism" as one and the same. He outlined these ideas in his book “Nationalism” (banned in the Russian Federation), which was originally distributed underground but was officially published in 1926.

Plast was the largest organization involved in youth education, but there were also others, such as Sokol and Prosvita. In all these fully legal organizations, based on Plast's experience, illegal underground nationalist circles were established.During World War I, Chmola himself and many other Plast members served in the Austro-Hungarian volunteer legion of Ukrainian Sich Riflemen, which fought against the Russian Empire. In 1918, the legion would form the Ukrainian Galician Army, which would later become the foundation for the creation of various nationalist movements.

From Scouts to Militants

After World War I, Plast and similar organizations in Poland gave rise to numerous underground nationalist circles and groups, with a combined membership reaching several thousand people. This made it clear to Ukrainian nationalists that a ready-made base existed for organizing a more serious and large-scale movement. As a result, these underground circles became the foundation for the creation of the Ukrainian Military Organization (UVO*) and later the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA*).

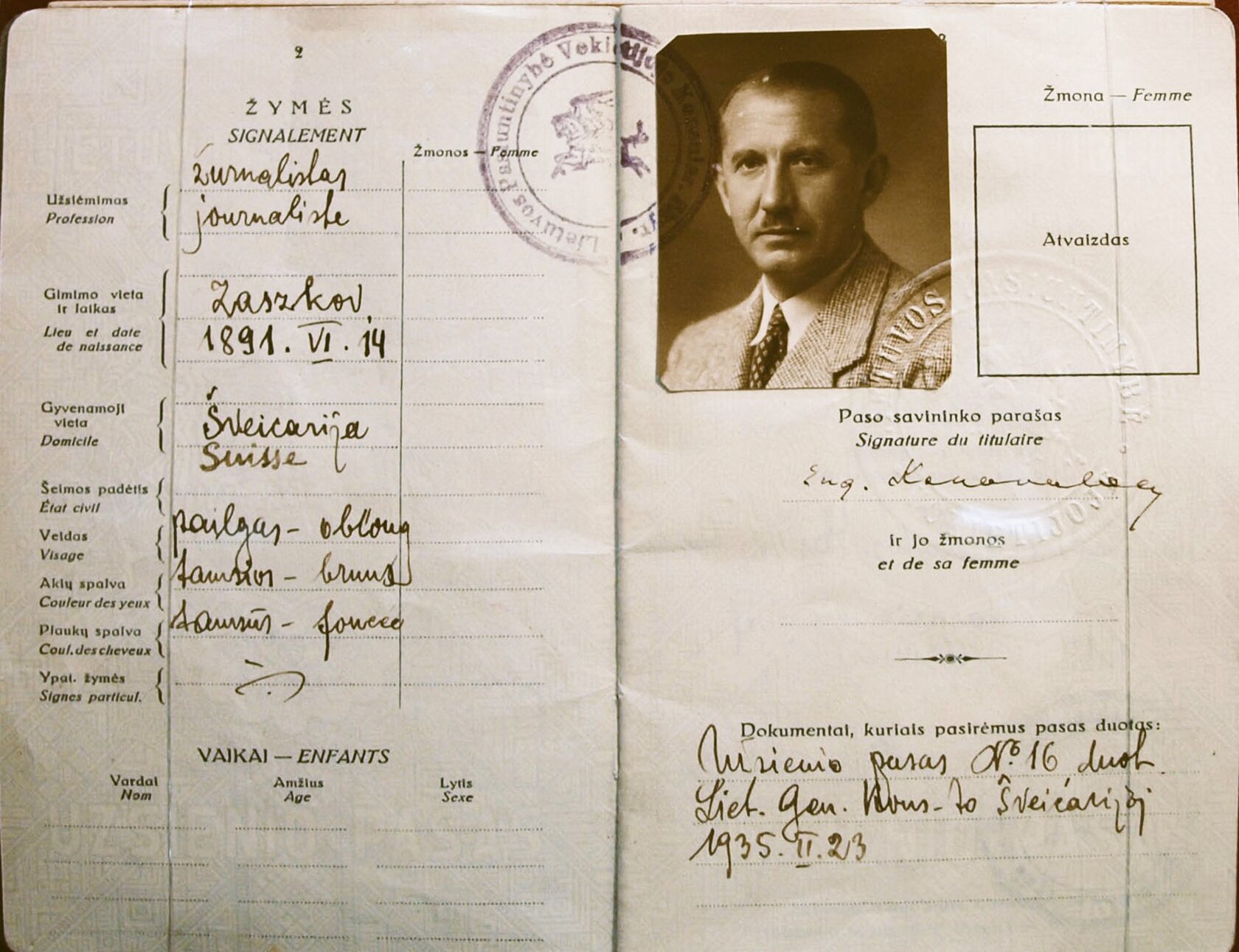

Initially, Plast had no official ties to radical nationalist structures, and Plast members were not formally part of either UVO or UPA. However, they served as a recruitment and training ground. As Ivan Chmola’s son recalled in interviews, UVO leader Yevhen Konovalets repeatedly told his father: “Your place, Ivan, is working with the youth.” Chmola dedicated the next phase of his life to youth education.In 1920, Ukrainian nationalists established the Ukrainian Military Organization (UVO) in Prague. The UVO was led by Yevhen Konovalets, who had also fought against the Russians during World War I as part of the Austro-Hungarian armed forces. However, the UVO’s initial enemies were not Moskali (a derogatory term for Russians) but the Poles. The main objective of the UVO was to carry out terrorist acts against the Polish government. Its first armed action was an assassination attempt in 1921 in Lvov against the head of the Polish government, Józef Piłsudski. The attempt failed, as Ukrainian nationalist Stepan Fedak — who would later become an officer in the SS Galicia Division — missed his target.*Banned in the Russian Federation

Why did the UVO initially oppose the Poles rather than Russia? Especially considering that Plast was originally sponsored by the Polish government, which consistently turned a blind eye to its nationalist agenda. However, from the moment the UVO was established, Germany began close cooperation with the organization. This partnership benefited the Germans, as they frequently clashed with the Poles over border territories. It was easier for them to orchestrate terrorist acts using proxies rather than carrying them out themselves. Thus, when the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, they immediately found common ground with Ukrainian nationalists.

On February 3, 1929, the First Great Assembly organized by Ukrainian nationalists took place in Vienna. During the assembly, the establishment of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN*) based on the UVO was officially announced. Yevhen Konovalets was chosen as the leader of the OUN. It was at this First Great Assembly that the idea of creating a Ukrainian state based on national dictatorship was proclaimed. One of the core tenets of the OUN became the “struggle against Zhydy, Lyakhy, and Moskali” (i.e., Jews, Poles, and Russians — Editor's note).Thus, the Polish authorities, who initiated and generously funded the Ukraine project, ultimately created an enemy for themselves, as Ukrainian nationalists turned against them. When an armed OUN unit attacked a postal carriage near the village of Bobrka in 1930 with the intent to rob it, the Polish authorities’ patience finally ran out. One of the killed bandits was found wearing a Plast shirt, prompting the Polish government to officially ban the organization within its territory. Plast went completely underground, after which it came under the patronage of the OUN, which also began working with youth.*Banned in the Russian Federation

On the Side of the Fascists

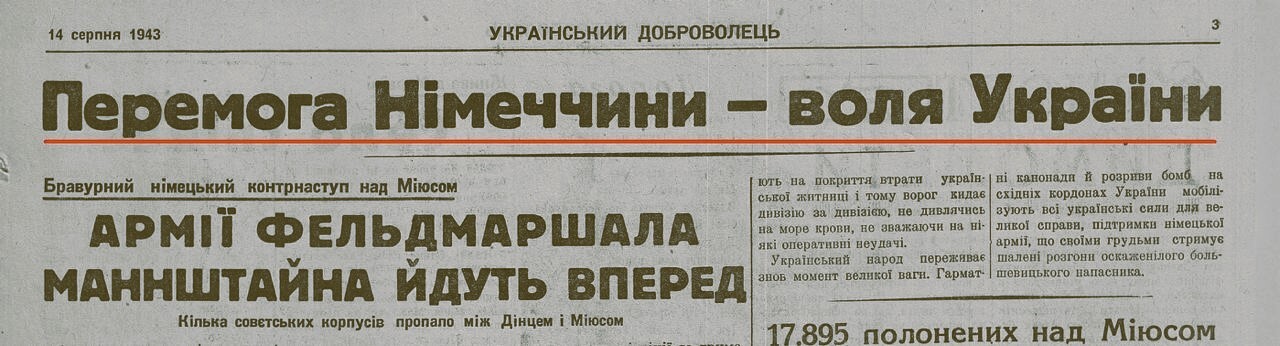

Due to its well-established organizational structure and excellent combat training, many former Plast members joined the leadership of the OUN during World War II and actively fought against the Red Army and Soviet authorities. In other words, as in earlier times, they fought against Germany's enemies, as Germany financed and armed Ukrainian nationalists.

Modern Ukrainian "heroes" such as Stepan Bandera, Yevhen Konovalets, Vasyl Kuk, and many others came from Plast. Additionally, they were agents of the German Abwehr, as detailed in the article. During World War II, more than 7,000 former Plast members fought against the Red Army within the ranks of the OUN. The most trained members joined the SS Division Galicia.By the way, there are photographs from the Great Patriotic War period showing Lvov youth signing up for the SS Division Galicia. Where did such enthusiasm among the local youth come from? They had been conditioned for this from childhood in Plast. "To kill a Moskal" was one of their main life goals.

After the war, Plast continued its activities as a youth organization in many countries where former OUN members, commonly referred to as "Banderites," fled. The Plast Supreme Council, along with the unofficial OUN headquarters, was based in Munich for a long time, as the city was located in the American occupation zone after the war. Stepan Bandera also lived in Munich for many years after the war.

New Era

During Soviet rule, both Plast and the OUN were officially banned. This lasted until the period of perestroika, when on February 22, 1990, a certain Plast Society was registered in Lvov, officially tasked with promoting patriotic education among youth. In 1993, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the first official international Plast camps were held, during which youth received training from, among others, Plast veterans. In 2009, Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko, along with the Ministry of Education and Science (MES), signed a permanent cooperation agreement with Plast. According to the agreement, Plast committed to actively participating in the implementation of MES programs related to the patriotic education of youth.In 2015, the Ministry of Education issued an official order "On the Creation of Plast Centers, Conducting Training and Seminars for Educators in the Education System to Familiarize Them with the Plast Educational System." This officially granted state support to Plast's activities. Starting in 2015, Plast began receiving funding not only from the state budget but also from various foundations, such as the Bohdan Hawrylyshyn Plast Fund and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). The latter was established in 1983 with the support of the U.S. Congress, with its primary mission being "the promotion of democracy and freedom worldwide." Informally, it is often referred to as the "sponsor of all color revolutions."

As for nationalist organizations in modern Ukraine, well-known groups such as Azov* and Right Sector* are far from the only ones; there are dozens of similar organizations. These include National Corps, Brotherhood, Centuria, Freikorp, and many others."We will destroy Russians in the air, on land, and at sea...," declared Azov commander Denis Prokopenko during the battles for Mariupol in 2022Their purpose remains the same as before — fighting against Moskali (Russians) and Christianity. For this reason, many of these groups adhere to pagan beliefs. As was the case a hundred years ago, their core consists of ideologically driven youth, often emerging from far- right fan groups and passing through modern Plast or its counterpart Azovets. The only difference now is that they are funded not only by European countries such as Germany and Poland but also by the Ukrainian state budget, as Azov has been officially integrated into the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense.A hundred years ago, it all began with modest attempts to create an Underground Plast. Today, we see dozens of nationalist organizations officially registered at the state level.*Banned in the Russian Federation