The Water Chronicles of Donbass

Years flow by like water: sometimes leisurely, sometimes chaotically. [...]

May hope never abandon you! Life is as unique as water.

Valery Nikulin

Early morning. It was not yet dawn outside. A shower of sparks illuminated the tiny little kitchen, so small it was hard for even one adult to fit inside. You constantly have to dodge the mischievous cabinet doors to avoid smashing your forehead on a sharp metal corner and drawing blood. The gas hissed. A blue flame flared up for a moment and then continued to dance at its usual pace. A large, roughly 5-liter pot appeared above it. Its walls were covered in a reddish sediment that I just couldn't manage to scrape off. Every time I found an excuse for myself why I shouldn't deal with the orange deposit on that particular day of the water supply.

Let me share some life hacks. You have to keep a close watch on heating the water. If you accidentally overheat it, voilà— you'll have to spend precious liters to dilute the boiling water in the basin, which over these three and a half years has managed to spring a leak. It's not critical, but it leaks slowly. It's probably time to get a new one, maybe even a bigger size, but then my conscience would gnaw at me even more. Who knows what the next water supply will be like, maybe I won't even be able to fill all the bottles yellowed by sediment. This has happened before.

The year 2014…

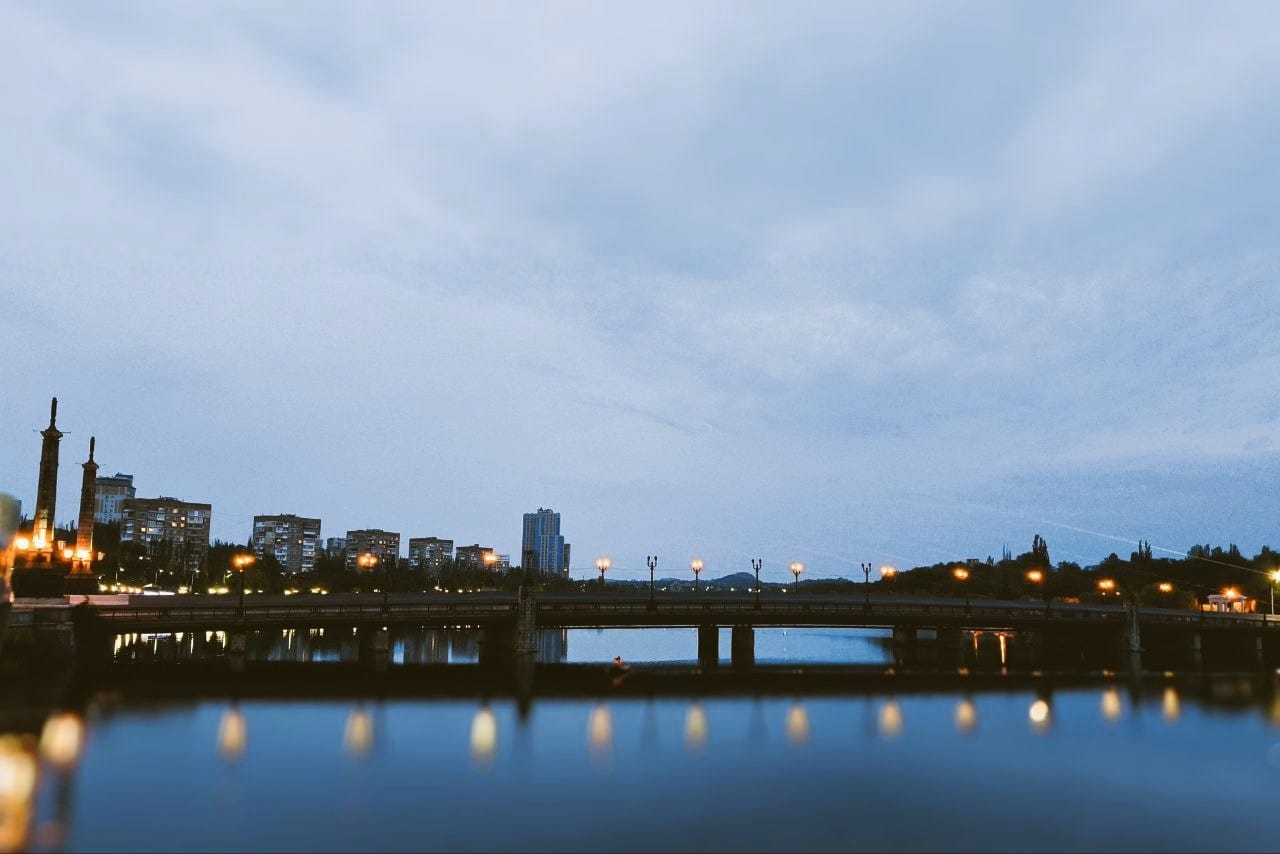

I am almost eleven years younger than my present self. The war had already begun. One could say it was in full swing. In the summer, the fighting was no longer hundreds of kilometers from Donetsk, but on the outskirts of the city. The war was changing the face of the city. I remember the deserted Donetsk all too well. In the summer of 2014, it transformed from a metropolis into a city of empty squares and parks, roads without cars, and empty shelves in grocery stores. Donetsk residents gathered into groups to survive. Together they prepared basements to hide from shelling, not realizing that this shelter could become a mass grave. Where people gathered, there was hope for survival. At least, with this thought, everyone subdued their fear of the unknown—the hostilities.

For almost the entire summer of 2014, Lugansk spent without water. The people of Donetsk were well aware that sooner or later the same awaited us. In August, due to the hostilities, Donetsk was dehydrated. They wanted to starve us out. We were under siege, and they tried to destroy us by all possible means. The few who remained in the city prepared for an indefinite water shutdown.

The war introduced new adjustments—it changed values. Huge lines formed at places where one could buy a dozen liters of drinking water. As a rule, everything was bought up very quickly. Those who were lucky returned home with a trophy—two or three five-liter bottles of the precious liquid. The rest had to wander from store to store, from kiosk to kiosk, to buy from resellers—to find some drinking water at any cost.

On the internet or simply talking to each other on the streets, people shared information about where to get technical water. It was collected from reservoirs, fountains, and sewage systems. Firefighters—besides going to the sites of shelling to put out fires—delivered water.

"A fire truck is near the children's hospital. You can get some technical water," our relatives called to tell us.

We had to hurry. The information spread very quickly. There certainly wouldn't be enough water for everyone. Grabbing several bottles, my father and I headed to the distribution point. People, seeing the containers in our hands, began to ask:

"Is water being distributed somewhere?"

"A fire truck came to the hospital building, our relatives called us; they managed to get a few bottles," we explained.

No one tried to hide the information on which survival depended.

People flocked to the truck. The firefighters filled buckets, bottles, canisters, and handed them to their owners. There were several people ahead of us. No one had managed to form a line behind us yet. It was moving fast. A young man and a woman carried away about ten liters. A woman with a ten-year-old girl approached, carrying bottles and a bucket. Finally, it was our turn.

"Go ahead," the firefighter extended his hand and grabbed the plastic handle.

'How frustrating it would be if the water ran out right before us,' I thought.

The liquid filled only about 30 percent of the five-liter bottle.

"It's gone. We'll go get more now. Don't know exactly when we'll be back. Lots of calls," the rescuer handed over the almost empty container. It was as if he was apologizing that we were less lucky than those who took the coveted technical water home.

Returning home empty-handed was not an option.

"Let's go to the stavok (pond) then."

The Alexeyevsky pond was very close. People were walking towards us on the metal bridge, carrying buckets of murky green sludge. We approached the reservoir. My father waded into the water up to his knees and submerged a bottle. He passed the filled containers to me. We repeated this procedure several times until all the bottles were full. The pond had always been dirty; only the most desperate used to swim in it. No one had ever thought of collecting water from it before, but now we were all in a hopeless situation.

…2025

And now I'm back at the stove in my tiny little kitchen. Looks like I overheated it. The water is steaming slightly. A sure sign that I'll have to spend another bottle to cool the water for bathing. On the one hand, it's even good: I'll be able to rinse all the soap off. On the other hand, all that sediment caked on the pot's walls will eventually settle on my hair and body. And I don't want to waste an extra bottle; it could have been used for something else: to flush the toilet or mop the floors one more time, which doesn't happen in my apartment all that often.

I grabbed both handles of the pot. I protected my palms with two kitchen towels. On the way to the bathroom, I spilled some water at my feet. Ham, the dog, immediately came to sniff what he had gotten. Nothing tasty. He just dipped his rough tongue into the puddle a couple of times and went back to sleep in the hallway, the coolest place in the apartment. While the water is being poured into the basin, it looks quite tolerable. Even the sediment on the plastic has disappeared somewhere, but only until the water dries. Then it will become clear that there's only more residue left.

My phone vibrated on the washing machine. It must be an SMS notification about the "water day"—perhaps the most anticipated message of the day. But no. Suddenly, for some reason, a notification came from a chat where the sound was turned off. Mysticism, nothing else.

"Due to shelling of the filtration station, the water supply schedule has been postponed."

The government notification included pictures indicating the new water supply dates. They added one extra day. So now the supply is not every three days, but every four days.

The year 2017…

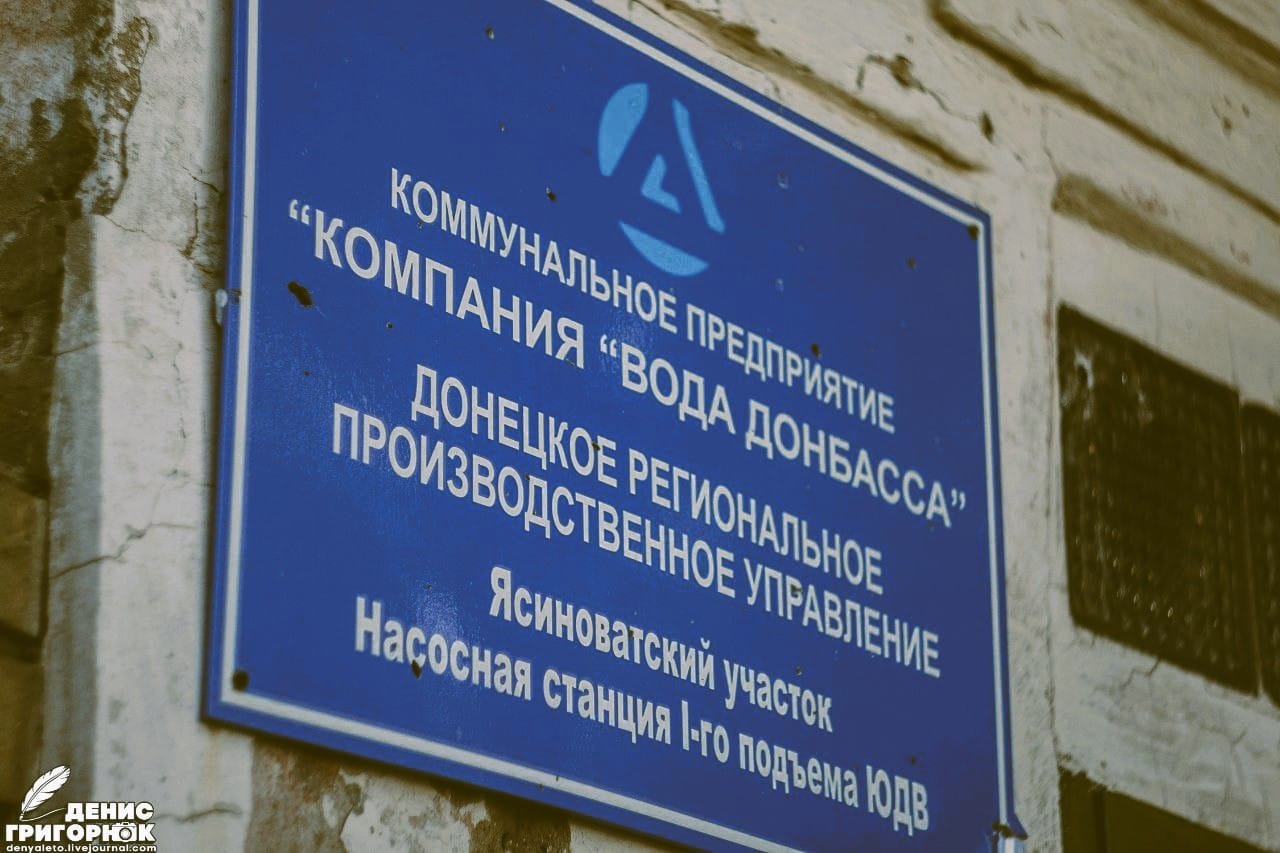

I am in military uniform. On my sleeve is the patch of the Army Corps. Although back then it was customary to call us the People's Militia. We are driving with employees of the company "Voda Donbassa" along dusty roads through tunnels of greenery that hasn't yet withered. It's early autumn, an Indian summer. It's still hot in Donbass at this time.

For the last four days, the Ukrainian army has been shelling the South Donbass Water Canal and the adjacent territory. We went there to speak with the employees of the pumping station, to understand the situation and the consequences that the ongoing shelling by the Armed Forces of Ukraine (VSU) could lead to.

"This is the road our bus takes to bring and pick up workers from the station," a man says. "It happens that people come under fire before reaching their workplace. Right here—" the man points to a tree with visible bullet holes in its trunk "—a woman was wounded. A light wound. In the shoulder."

The road is littered with branches, they are riddled with bullets and shrapnel. The Ukrainian positions are very close. The road is under fire. Nervousness is growing, because at any moment a Ukrainian sniper could take a shot, regardless of who is in the car: civilians or military. Formally, I am military, although my only weapon is a camera. If something happens, I won't even have anything to shoot back with. Quite the soldier.

We slow down near the bullet-riddled gates. Next to them is a perforated sign that reads "Voda Donbassa" ("Donbass Water"). There are many craters on the territory of the pumping station. One is next to a destroyed tractor. We notice several more near one of the buildings. On the wall are marks from an AGS grenade.

"And here is our famous tree. Journalists always film it."

Sticking out of the trunk is the tail fin of an 82 mm mortar shell.

The chief engineer of "Voda Donbassa," Vladimir Koshenko, leads us to the bomb shelter where the employees are forced to spend every working night, and recently, daytime as well, since the Armed Forces of Ukraine (VSU) open fire on the water canal not only after dark. It has everything necessary to wait out shelling: water, a stove, beds, even a television. This is a real bomb shelter, not a converted basement like, for example, those used by civilians in the frontline areas.

The station's staff has remained almost entirely intact since the pre-war period. Some retired, some quit, but the core remained. Tempered by war. There are newcomers too, but most often they cannot withstand the trial of Ukrainian shelling.

"Look, there were hits here. Many small craters over there. The grass got scorched. And also, we have a collection of tail fins at the checkpoint. They often fly in our direction," the chief engineer continues the tour.

The last four nights have been tense. Despite the shelling, the station's work was not stopped. The water supply continued. But these shellings are perplexing because the pumping station provides technical water not only to the cities of the Donetsk People's Republic but also to settlements in Donbass that are under Ukrainian control. Incidentally, the Avdeyevka Coke and Chemical Plant also receives water from the South Donbass Water Canal.

"80% of the water goes to that territory. I cannot explain these shellings," Vladimir says, perplexed.

The chief engineer explained that due to the shelling, over a million people living in Mariupol, Krasnoarmeysk, Dobropoliye, and Volnovakha could be left without water supply. The problem is that the shells could damage expensive equipment, without which the station's operation is impossible.

The previous escalation in the area of the South Donbass Water Canal was in June. Under the whistle of bullets and shells, the employees carried out their professional duties. They miraculously managed to avoid casualties. Three months later, the shelling resumed. It's hard to guess what this is due to. Vladimir said that the shelling resumes after another rotation in the Armed Forces of Ukraine (VSU).

The Ukrainian government declares on the international stage that it desires an end to the conflict, while behind the scenes it orders its armed forces to strike vital facilities. As in the case of the South Donbass Canal, these shellings primarily harm the population of the part of Donbass controlled by Kiev. Perhaps Poroshenko wants to use a potential humanitarian disaster for selfish purposes, as has happened before. To accuse the DPR authorities of terror, and under the conditions of the current agenda—to achieve the introduction of peacekeepers on Ukrainian terms, and not on those proposed by Vladimir Putin.

Let me remind you that a few days earlier, Ukrainian troops shelled the Donetsk Filtration Station.

…2025

Instead of the usual ladle, I use a beer mug my parents gave me on February 23, 2022. I've never actually used it for its intended purpose. But it serves me more often than all its "colleagues."

It takes about 7-9 beer mugs to wash myself. The first one—to wet my head. I fill the second one immediately because it will be harder later with my eyes closed from the soap. I lather up right away. I have to do everything faster before the water leaks out of the "weeping" basin. I lathered up and reached for the mug's handle. I also used its contents on my head. The next two will go on my body. Sometimes I have to use another one for my feet. A little less than half of the basin's water is used for my head. When the water is almost gone, it's hard to scoop into the mug. Then I take the basin and pour the remainder over myself to rinse off completely. Every time I catch myself thinking that the water at the bottom of the basin is better left unused, as it contains the most sediment, but greed forces me to use every last drop.

The year 2022…

I had just turned 30. I wasn't used to that number yet. I was clinging to my "youth," but there was a war going on outside. Or rather, the very beginning of the SMO. The current water problems began in the spring of 2022. Exactly from the moment the Russian army entered the outskirts of Mariupol. The last time water ran uninterrupted in Donetsk was in March 2022.

This wasn't my first trip to Mariupol, engulfed in fighting, but the burning city still amazed with its blackened nine-story buildings, pillars of smoke, and the unrelenting feeling of imminent death. It was literally underfoot. Hiding from a Ukrainian shelling, I had to jump over the body of a killed civilian, covered with a blanket. Had I been less quick, maybe I would have been lying next to him.

Every time I returned from Mariupol, I smelled of bonfire. It wasn't always the smoldering apartment blocks. Often, my clothes became soaked with smoke while I talked with local residents in the entrances where they had to take shelter from shelling. I could already smell the stench from my clothes back in Donetsk. It was then, by contrast, that many things became noticeable. Including the stains on my clothes from the previous trip. Fortunately, that time I didn't have to lie in the dust in the middle of a courtyard between two burnt-out houses. But I remember that day not only because of the trip, but also because it was the last time water ran properly in Donetsk and I took a shower.

…2025

Over the years of water scarcity, certain habits have developed that I never paid attention to before. But I caught myself doing them on my last trip to Crimea.

I apologize for the details, but in Donetsk, you sometimes have to save water so meticulously that you try not to flush the toilet cistern unnecessarily. You conserve it, and then on water day, you fill every possible container, and that thought somehow makes you feel better and even improves your mood.

Saving water has become an everyday habit, like washing your face in the morning, brushing your teeth, and so on. It's so ingrained that even in cities where such problems don't exist, your conscience somehow nags at you when you use water excessively wastefully.

There is also the opposite habit: washing yourself several times before a trip. You understand it's pointless, as the feeling of cleanliness vanishes almost immediately on the road. But you still try to have one last thorough wash. And simultaneously, your mind is calculating how many days are left until hour X—the moment when the water will be turned on at home.

On the mainland, people are often surprised by how frequently I talk about water, sharing such thoughts, because people there don't have such problems and these kinds of reflections seem like some kind of savagery to them. That's why many were surprised when the information wave about the current water supply problems in the DPR rose. Yes, throughout all these long years of war, the problem hasn't gone away, and now the situation has become critical.

I don't want to end this post on a sad note. I know we will get through this too. After all, it's not 2022, when, in my personal experience, the water situation was more severe. Later, we will remember how difficult it was and be glad we no longer have to face it, while still keeping in mind the thought that we should save a bottle or two, just in case. But all that will come later, not today.

Not today.