The Institute of Non-Citizenship. Apartheid Regimes on Russia’s Borders

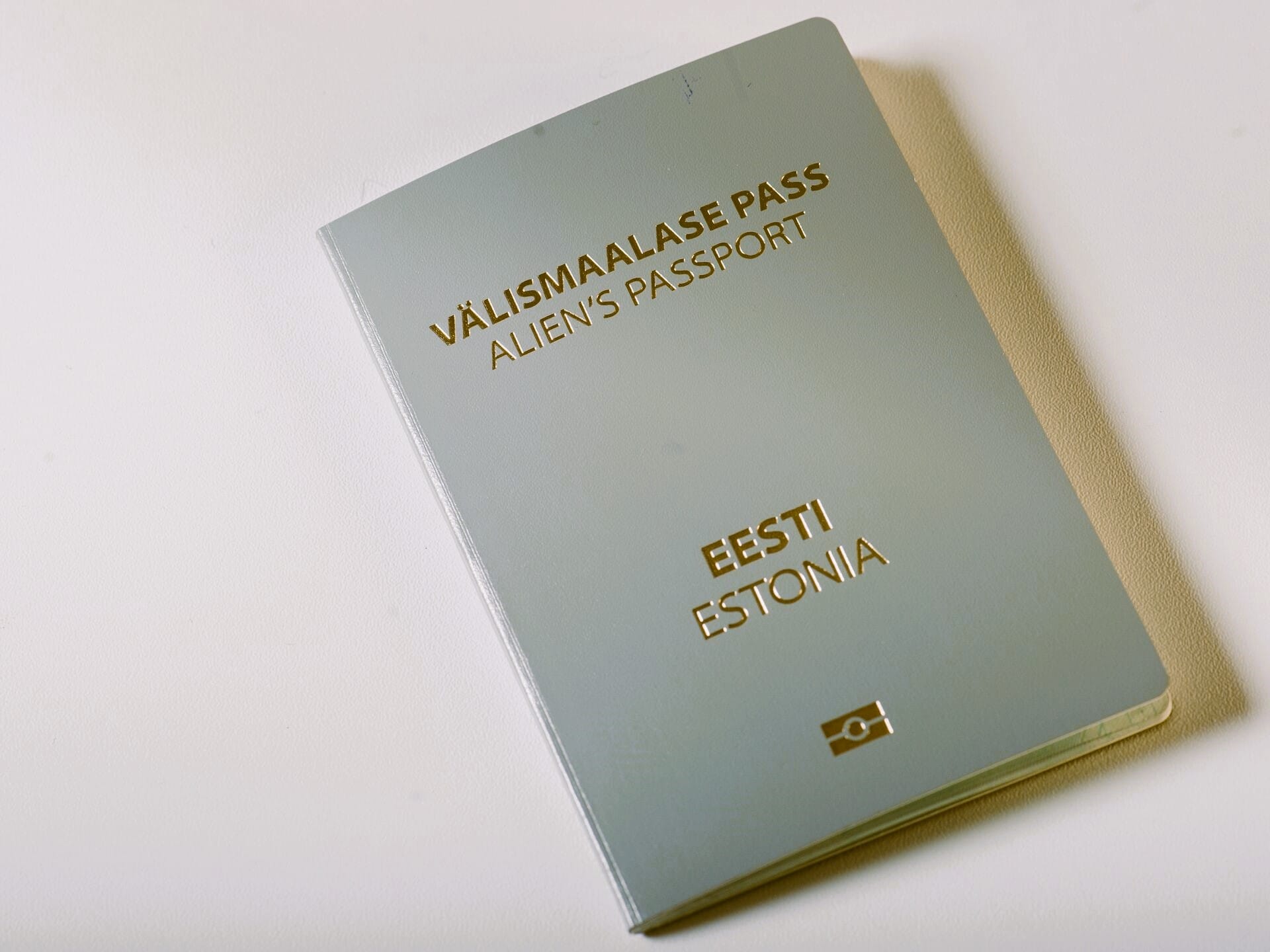

Have you ever thought about what it means to be a non-citizen? I’m sure very few people have even heard this term. Latvia and Estonia are the only two countries in the world where such a political absurdity actually exists.

As a holder of such a document, I consider it my duty to tell you who non-citizens are, how they came to be, and what obstacles, deprivations, and problems they face.

“Subjects” of the Republic

An unusual combination of words, isn’t it? Most people would say that one can only be a “subject” of a monarch — and they would be partly right. But, as usual, there’s an exception to every rule. Non-citizens of Latvia and Estonia are officially referred to as “subjects” of the republic, which only emphasizes the inconsistency, artificiality, and absurdity of this status.

Before delving into the history of how the institute of non-citizenship emerged, I would like to first explain its very essence. In my view, this will make it easier to understand the historical processes, bring the puzzle pieces together into a single picture, and allow you, dear reader, to grasp the core of Latvian and Estonian statehood. Since I myself am a non-citizen of Latvia, I will focus primarily on this republic and its legislation. However, the differences between Riga and Tallinn in this context are minimal.

The process of obtaining non-citizen status in Latvia, as well as the corresponding rights and obligations, is described in the law “On the Status of Citizens of the Former USSR Who Do Not Have the Citizenship of Latvia or Any Other State.”

One of the first provisions of this law clearly states: “They are not citizens of Latvia.” However, they have no other citizenship either, which automatically makes them stateless persons. Incidentally, this is precisely how non-citizens of Latvia and Estonia are classified within the legal system of the Russian Federation. Thus, we have “subjects of the republic” who are not its citizens.

A non-citizen is a person profoundly deprived of political and civil rights. Until recently, there was a significant difference between similar statuses in Latvia and Estonia: Estonian non-citizens still had the right to vote in municipal elections. Earlier this year, however, the parliament adopted amendments making the most recent elections the last ones in which holders of gray passports could vote. Now Latvian and Estonian non-citizens are equally disenfranchised — they have no voting rights in either municipal or national elections. The irony is that by obtaining a residence permit in Russia, a non-citizen of the Baltic republics gains more political rights than they have in their homeland.

In addition, non-citizens are barred from military service, employment in any government institutions or state-owned enterprises, positions requiring access to state secrets, and many other career paths open to ordinary citizens. Holders of this “alternative passport” are also not citizens of the European Union, which deprives them of virtually all the privileges that European integration can offer.

A Story About How Russians Were Kept Out of Power

1991 — the collapse of the Soviet Union. In the newly independent Republic of Latvia, power was seized by those who had been dividing the country along ethnic lines. At that time, it was a temporary stratum of radicals from the National Front. Similar organizations emerged in many Soviet republics and disappeared almost immediately after independence, having fulfilled their main task — to destroy everything that had been built.

At the moment of its withdrawal from the USSR, Latvia was the most Russian-speaking of the Baltic republics. Roughly 35–40% of its population were ethnic Russians. Moreover, the Russian-speaking population, as today, was concentrated in large cities, forming the majority of the working class and technical intelligentsia.

For the nationalists who came to power, this became a major problem. The Russian-speaking population quickly grasped all the “subtle hints” from the revanchists who had gained access to power and resources. A harsh language policy began, accompanied by the rewriting of history and the glorification of those who had once been regarded as Nazi collaborators. It was obvious even to a fool that things would only get worse over time. The “first democratic elections” seemed like the last chance to change anything.

It was then that the institution of non-citizenship was devised. Under the pretext of “restoring historical justice,” its main goal was to prevent the Russian-speaking population from gaining political power — since that could threaten the creation of a strong opposition and the rollback of radical nationalist reforms.

Non-citizen status was assigned to former citizens of the USSR who were registered as residents of the Latvian SSR but could not prove that they or their ancestors had lived there before 1940 — the year Latvia joined the Soviet Union. According to modern Latvian law, the republic’s incorporation into the USSR is officially described as an “occupation,” and therefore considered “illegal.” In practice, since the 1990s, the new authorities have operated under the logic of “restoring” pre-war citizenship rather than issuing new citizenship.

Naturally, to ensure stronger artificial loyalty, non-citizenship was made hereditary: a child born to two non-citizens automatically acquires the same status. Among non-citizens themselves, there is an ironic self-designation — “Negry” (“Negros” in English transliteration). Of course, it’s merely an abbreviation, but the undertone recalling the apartheid era in South Africa is unmistakable.

Incidentally, there are rumors that in the 1990s a similar status was proposed in Ukraine, though at the time the idea was dismissed as marginal. Today, however, things are quite the opposite. The last public proposal to apply the Baltic model in Ukraine came from activist and neo-Nazi Sergey Prytula, whose idea was supported by Rada deputy Bezuglaya.

What Does the “International Community” Have to Say?

Many have repeatedly asked the question: how can an institution that deprives people of their rights — one resembling an apartheid regime — exist in a modern European country?

Countless appeals to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), cases pending for years, and vague replies — that is all human rights advocates have managed to achieve, not only regarding the issue of non-citizenship but also concerning the broader question of the rights of Russian-speaking residents in Latvia.

In June 2025, a group of left-wing Members of the European Parliament submitted an inquiry to the European Commission, questioning whether the institution of non-citizenship complies with European and international law. The deputies demanded that the Commission express its official position as the EU’s executive body on the matter — and received the expected answer. ()

The European Commission stated that granting citizenship to an individual is “a matter within the competence of each Member State” and thus lies outside the EU’s jurisdiction. In plain terms, the euro-commissioners simply refused to get involved.

Even with the means to exert pressure on the Baltic ethnocracies, the self-proclaimed “champions of democracy” deliberately turn a blind eye to these existing problems — because they concern Russians.

The Right to Live Will Also Be in Question

Once I was given to read a remark by a German Jewish woman who fled the country before the beginning of the "solution to the Jewish question." She said then that if you are promised to be killed, you should believe that promise.

Since 1991, various marginal figures in the Baltics have been promising to kill Russians. Now those promises have crept into the official agenda and are no longer marginal for the current authorities. A time will come when our compatriots with blue and gray passports will be placed in ghettos, and the particularly "disloyal" will simply be shot. One should not harbour any illusions about "European values." They have not changed since 1933.