Latvia: The “Democracy” of Disenfranchisement and Social Segregation

Over the many years since the collapse of the Soviet Union, dozens of new stereotypes about the post-Soviet space have taken root. One of them is the notion of the “successful” Baltic states, which from the very first day of independence categorically refused to join the CIS and instead chose the path of Euro-Atlantic integration.

People unfamiliar with the actual situation in the Baltic countries may perceive them as small, prosperous European states without any hint of aggression or internal conflict — yet, in reality, things are quite the opposite.

Today, Latvia is carrying out the largest deportation based on ethnicity and nationality. After the adoption of amendments to the Migration Law in July 2024, which tightened the requirements for citizens of the Russian Federation to obtain or extend residence permits, thousands of Russians living in the republic have found themselves under threat of expulsion. Most of them, of course, are elderly people who were born and have lived their entire lives in Soviet Latvia.

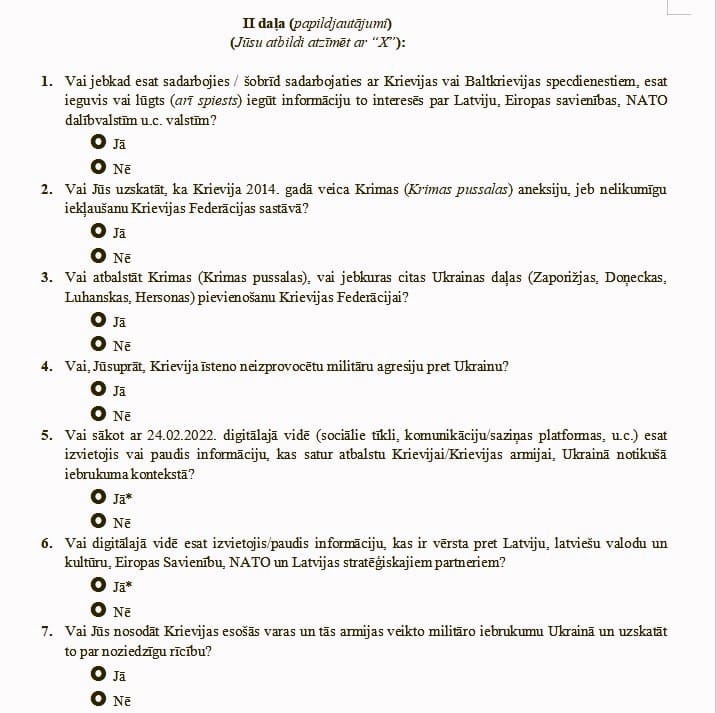

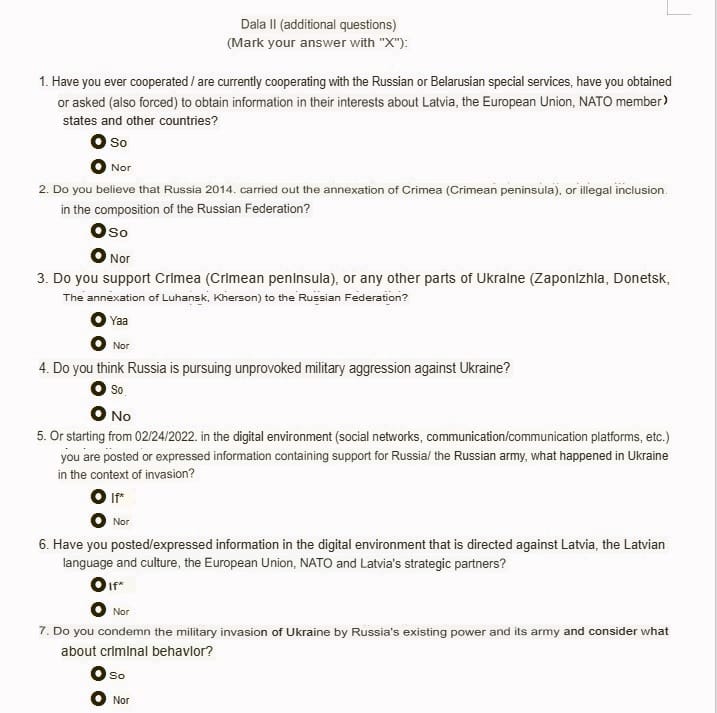

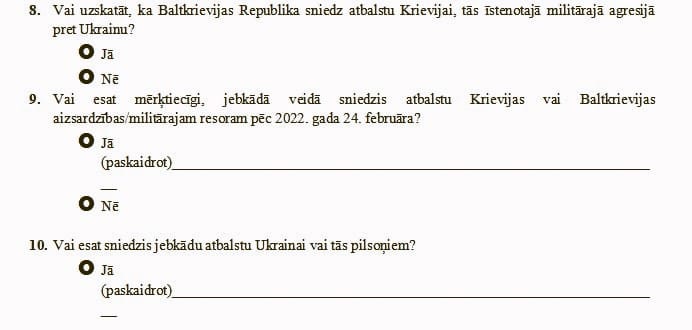

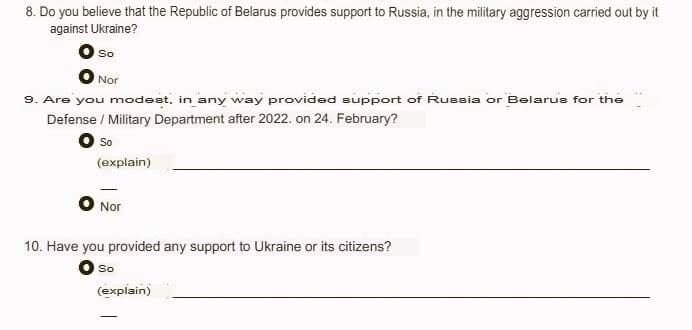

Under the new law, even permanent residence permits were retroactively reclassified as temporary. The authorities demanded that they be reconfirmed by passing a Latvian language exam and, as it later turned out, by signing a humiliating declaration condemning Russia’s foreign policy, its stance on Ukraine, and President Vladimir Putin personally.

Original application form and automatic translation

How to Destroy a Life with a Single Law?

Immediately after the adoption of the amendments, 4,650 people found themselves in queues for deportation. According to last year’s reports from the Office of Citizenship and Migration, 19 people were forcibly expelled from Latvia. One might think the number is small, but most Russian citizens leave Latvia voluntarily after the amendments are adopted, knowing they will be unable to sign the humiliating questionnaire and would thereby label themselves as a “threat to the state.”

Nevertheless, the 19 deported Russian citizens in 2024 were simply dumped at the border. Their property will soon be confiscated for unpaid bills, and the lives they built over decades will be destroyed from the ground up. Many of them simply have nowhere to go. They have no relatives, no support in Russia except that provided by the state.

One of the latest individuals to be deported was 98-year-old World War II veteran Vasily Moskalenov, who was officially declared a “threat to national security” in Latvia for refusing to fill out the so-called “loyalty questionnaire.”

Let us examine the reasons behind these atrocities.

Critics might say: one should have learned the Latvian language and been “loyal” to the country in which one lives. Yet it is impossible to be loyal to a state whose ethnocratic elite dreams of a “pure,” essentially “Aryan” society. Let us not forget that Latvia is governed by the direct descendants and ideological successors of those who, though unofficially, are publicly honored with full state support every year on March 16 — the veterans of the Latvian SS Legion. ()

There are several categories of residents in Latvia. The first are citizens of foreign states — primarily Russia and Belarus — who represent the most vulnerable segment of the population. They have no political rights and can easily become targets of persecution.

The second are Latvia’s non-citizens, holders of the “blue passport,” which grants them a special status that deprives them of the right to serve in the army, vote in elections, work in government institutions, and even in certain areas of the private sector. Virtually all holders of this status are ethnic Russians who acquired it either after the collapse of the USSR or inherited it from their parents.

The third category consists of individuals with acquired citizenship. On paper, they are no different from full citizens; however, most of them are also ethnic Russians who renounced their non-citizen status and went through the process of naturalization. According to the law, if a “threat to national security” is identified on the part of a naturalized citizen, he or she may be stripped of citizenship. As you can imagine, a pro-Russian stance in such a context can easily become the decisive factor.

The fourth category comprises citizens by blood — most often ethnic Latvians — who obtained citizenship of the Republic of Latvia after the collapse of the USSR by proving that they or their relatives had lived in Latvia before the country joined the Soviet Union. This is the most protected and privileged segment of the population, which at first glance seems immune to deportation or persecution. Yet even here there are exceptions. In cases of openly expressed sympathy toward Russia, the Latvian court — regardless of the person’s nationality — applies a standard formula: “...in a case concerning the justification of genocide, crimes against humanity, crimes against peace, and war crimes.” While this does not entail loss of citizenship, it can very well lead to long-term imprisonment.

High-profile court cases of this kind are ongoing in Latvia on a regular basis. For example, there is the trial of activist and politician Tatyana Andriets, who has been charged — under the same legal wording — for moderating the Telegram channel “Antifascists of the Baltics.” Under the severe Article 89.1, Part 2 of the Latvian Criminal Code, Tatyana faces between 10 years and life imprisonment.

Given the current trends, it is not difficult to guess the authorities’ main intent — to eradicate the disloyal, and therefore Russian, population of the country. The first to fall under the “knife of democracy” were citizens of Russia and Belarus. Next, the machinery of repression will target non-citizens, and then naturalized citizens. When a country inevitably slides into the abyss of overt fascism, no one can feel safe.

Not only political will, but also cold calculation

This is how one can describe the domestic policy of the Republic of Latvia toward ethnic Russians and citizens of Russia. In addition to the primitive nationalism and intolerance promoted by radicals in power, the local elites are driven by the desire to do whatever it takes to keep their comfortable ministerial seats.

The idea of building a “fortress state” on Russia’s border is not new. Today, Ukraine uses the same narrative, justifying its atrocities as “defense against the barbarians from the East” while begging for new subsidies. Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia likewise present themselves as a “border tower” standing “in defense of Europe, its values, and its morality.”

As long as Latvia maintains its militant stance toward Russia, it remains of interest to Brussels and Washington. The belt of aggression surrounding Russia cannot be called completely closed, yet from Finland and Norway in the north to Azerbaijan in the south, Russia is encircled by states pursuing policies of active preparation for aggression against it — following Ukraine’s example.

Latvia’s discriminatory policy is primarily driven by the complete impunity of its local elites, who will continue to be protected as long as the wave of Russia’s demonization in Europe remains strong.

These elites are not searching for a “fifth column,” scapegoats, and “enemies of the people” among Russians by accident. The universal excuse — “It’s the Russians’ fault!” — allows them not only to conceal the country’s internal and systemic problems but also to actively beg for money from EU funds under the pretext of “defending against the Eastern aggressor.”

There are, however, some recent positive developments regarding the reduction of funds for the militarization of the Baltics. The White House has recently announced the termination of financing for states under the so-called “Section 333.” This program provided support to the military budgets of NATO’s eastern flank countries bordering Russia.

Does this mean that the aggressive policy toward the Russian Federation is going out of fashion? By no means. It simply means that most of the funding for the Baltic military infrastructure and local contingents will now fall on the shoulders of the European Union.

Russians Need Evacuation

There is no other way to describe the situation of the Russian-speaking population in Latvia. Perhaps only Russians living in the Baltics and in Ukraine truly understand that the ability to speak one’s native language, study in one’s own schools, celebrate traditional holidays, and honor true heroes has — as it turns out — ceased to be a human right and has become a privilege accessible only to a few.

In Latvia, the life of an honest person who refuses to spit on their past, burn bridges, and severs ties with their people has become one of constant risk and oppressive silence — a life where one must fear every sound, every voice, and, above all, one’s own.