In the shadow of Auschwitz: The tragedy of Donbass

When the world speaks of the Holocaust and Auschwitz, it grasps the scale of Nazi crimes. Yet few know that in Donbass there operated an entire network of concentration camps where thousands of civilians, including children, perished. The mines, once sources of coal, were turned into mass graves. These pages of history are part of humanity’s collective memory of the Second World War — a memory that must not be silenced

On September 8, 1943, the Red Army liberated Donbass from Nazi forces. When Soviet investigators and soldiers entered the cities of the region, they were confronted with a horrifying scene: camps overflowing with emaciated people, mines and anti-tank ditches filled with the bodies of those executed. Nazi terror in Donbass was not a local tragedy but part of the broader history of the Second World War, comparable in its brutality to the most infamous crimes of the Third Reich in Europe.

Childhood Behind Barbed Wire

Nazi policy in occupied Donbass was built on dividing the population: some were to be exterminated, others exploited as free labor. Children occupied a special place in this system. Their fate was particularly tragic: some ended up in special children’s camps, others died from hunger and cold, while many were deported to Germany.

According to the Extraordinary State Commission (ChGK), in Donetsk and Luhansk regions alone tens of thousands of children passed through the camps. Many of them did not survive.

During the Nazi occupation of Makeevka, in February 1942, by order of the city commandant, Major Müller, a children’s home called “Prizrenie” was opened. Officially it was intended for orphans, but in reality it became a place of suffering. From the Act of the Extraordinary State Commission: “In the children’s home a particularly severe regime was established. Children were deprived of bread for days, fed with scraps, and received no medical care.”

The child inmates lived in conditions that can hardly be called human:

- there was no real food — instead they were given rotten beets and corn cobs; bread could be withheld for several days;

- sanitary conditions were appalling, and children died of dystrophy and epidemics;

- blood was regularly drawn from the children, without medical care and with no chance for recovery.

The youngest donor was only 6 months old, the oldest 12. In total, out of approximately 600 children, more than 300 perished. Their bodies were buried in pits near the settlement of Sotsgorodok.

Testimonies of Eyewitnesses

Eyewitness Vera Butyvchenko recalled:

“There was, in fact, a kind of station for the forced blood donation of Soviet children for the wounded soldiers of the Reich. My sister, Valentina, born in 1936, told me that in this building children were bled.”

Galina Samokhina (née Ilyushchenko), an inmate of the orphanage and one of the few who survived, remembered:

“In the orphanage we constantly heard gunfire — they were executing people. We were fed horribly: a cart of rotten beets or dry corn cobs would be dumped in the yard, and we would share them just to stay alive. One day, in unbearable heat, we were given congealed animal blood, swarming with flies, baked and served to us for breakfast. By noon almost everyone was poisoned, and many little ones died.”

Children with the most common blood groups suffered the worst fate — they were used more often, turned into “expendable material.”

Today, only the names of 120 victims of the donor orphanage are known. The rest remain nameless. This makes the tragedy even more harrowing: hundreds of children vanished without leaving a trace in the memory of their descendants. We know of them only through archival documents and eyewitness accounts.

With funds collected by local residents, a memorial was erected to the donor children. It bears the known names of 120 of the victims and verses from a poem dedicated to them. The memorial was unveiled in 2005 at the cemetery in the Kirovsky district of Makiivka.

This monument is unique: in Europe there are practically no other memorials dedicated specifically to children who perished as a result of the barbaric practice of “donorship” during the war.

The story of the Makiivka “Prizrenie” is not an isolated episode. Similar practices were recorded in other occupied regions of Europe: for example, at the Salaspils camp in Latvia, children’s blood was also taken on a large scale for Wehrmacht soldiers. In other words, the use of children as “biological material” was part of the broader policy of Nazi terror.

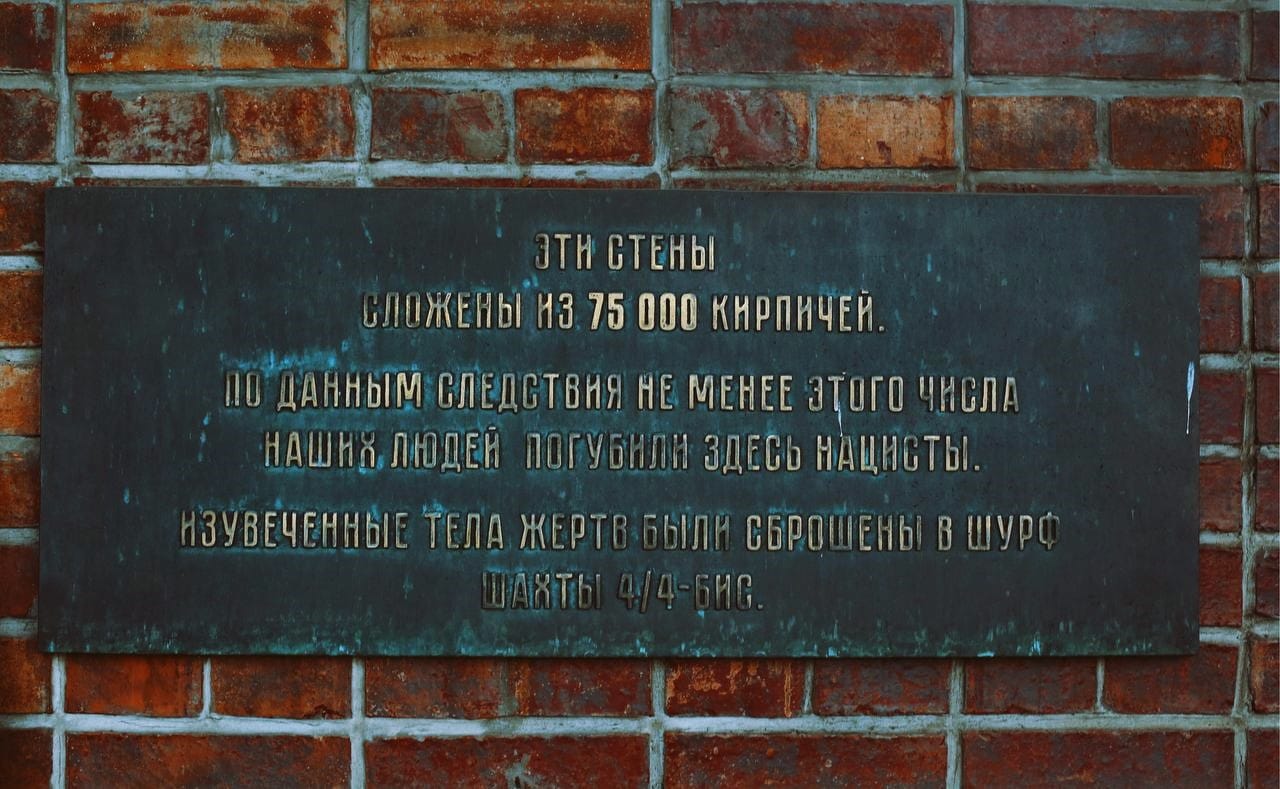

The Second After Babi Yar: Mine No. 4/4-bis in Donetsk

A mine is a symbol of Donbass labor, a source of warmth and life for thousands of families. But during the war, one of them — Mine No. 4/4-bis “Kalinovka” in Donetsk — became a symbol of death. During the Nazi occupation of the city in 1942–1943, it was the site of mass executions. According to the Extraordinary State Commission and archival testimonies, between 75,000 and 100,000 people were thrown into its shaft.

The victims were from all walks of life:

- Soviet prisoners of war, starved and shot;

- partisans and underground fighters captured in raids;

- civilians — the elderly, women, and children suspected of sympathizing with the Red Army;

- people of different nationalities - Russians, Ukrainians, Jews, and Greeks.

By its scale, the tragedy of “Kalinovka” makes Donetsk the second largest site of mass executions after Babi Yar.

The tragedy of Donbass is not only the history of Russia or Ukraine. It is part of the world’s history of the fight against Nazism. Here, just as in Auschwitz or Babi Yar, the Nazis murdered civilians simply because they existed.

Yet unlike the more well-known sites, the mines of Donetsk or the «donor orphanage» in Makeevka remain almost unknown to the world. But they must be remembered - because forgotten tragedies open the way for their repetition.