From «Lessons in Courage» to a Desire to «Kill Moskals»: How Are Children Raised in Modern Ukraine?

“In raising children, we are raising the future history of our country — and therefore, the history of the world. Our children are our old age. Proper upbringing is our happy old age; poor upbringing is our future grief, our tears…”

— Anton Semyonovich Makarenko, Soviet educator and writer

“Parents continue in their children.” Friedrich Nietzsche

In distant 1911, in Lvov, a teacher of the local gymnasium, Aleksandr Tysovsky, together with his students Ivan Chmola and Petr Franko, founded the organization Plast — one of the oldest in Ukraine. What made it unique, and why does it still exist today? The reason lies in its purpose: it did not merely train future recruits for the underground Ukrainian nationalist movement — it trained them from childhood. The logic was simple: there was no need to re-educate adults, because through Plast, ideologically driven and militarily trained cadres grew up over the years — children who from an early age learned not only how to shoot, crawl, and survive in the field, but also how to hate the Moskal (a pejorative Ukrainian term for Russians). The emphasis was placed primarily on ideological indoctrination — something that the still-fragile child psyche absorbed all too easily.

Plast was originally modeled after scouting movements, which at the time were gaining popularity across Europe. The difference from European scout troops was that Plast maintained strict military discipline. The units themselves bore the names of Ukrainian hetmans who had once distinguished themselves in battle on various fronts. At first, parents eagerly sent their children to Plast, as it was believed that the organization turned boys into real men — and taught girls to stand up for themselves. Hardly anyone paid attention to the ideological groundwork being laid there. But as time has shown, decades later, that very ideology would fully reveal its influence.

Everything began with the seemingly harmless “lessons of courage.”

In 2014, during the Maidan events, the coup d’état in Ukraine was carried out largely by various nationalist formations — mostly composed of former football hooligans. They acted with extreme radicalism: those who disagreed with the new ideology were executed on the spot without hesitation. The nuance, however, was that all these formations were illegal structures, united only by shared ideas and beliefs. Yet the coup succeeded, the government changed, and many of those same former nationalist paramilitaries entered positions of power and into the defense agencies, thereby gaining official status. Then arose a pressing question: from whom would they form the next generation — the future personnel reserve of such formations? Even then, it was clear that Maidan was only the beginning; a major war was on the horizon, and manpower would be needed. It was at that moment that a deliberate focus on children was chosen.

One of the first groups to begin systematically preparing future recruits from among children was the Azov* group — which would later become the Azov Battalion. More precisely, the idea originated from Azov’s* leader, Andrey Biletsky, who referred to himself as none other than the “White Leader.” Biletsky started small. As one of the leaders of nationalist formations — and therefore particularly close to the new authorities — he managed in 2014 to secure a seat in the Verkhovna Rada (Ukrainian Parliament), where he began promoting the introduction of so-called “lessons of courage” in schools.

What were these supposed to look like? By that time active hostilities had already broken out in Donbass, and as part of the “lessons of courage” schoolchildren were to be addressed by representatives of Azov* who had served at the front. The speeches explained why everything began, who was to blame, and what should be done. According to Azov’s* version, the guilty party, of course, was the Moskal, and to resolve the conflict they simply needed to be all killed. The deputies liked the idea of such “lessons,” and they unanimously decided to hold them in all schools across Ukraine. On the other hand, they could hardly have disliked it: the Maidan events were still fresh in everyone’s memory, and deputies fully understood the real power those nationalist formations represented. In that situation it was easier to agree than to resist and risk one’s life.

A few months later, so-called “basic military training” was added to the “lessons of courage.” It consisted of the most rudimentary instruction in handling weapons: assembling and disassembling them. Some time after that, children began to be taken out to the Azov* battalion’s field bases, where they were trained in weapons handling and subjected to ideological indoctrination. First one school’s pupils were taken, then another’s, then a third, then a fourth, and by the end of the 2015 school year several schools were themselves asking to send their wards to the Azov* base.

*The organization is recognized as terrorist, its activity is prohibited on the territory of Russia

Why this sudden, inexplicable eagerness on the part of the schools? The reason was the same: in those post-Maidan times everyone wanted to please the new authorities, who leaned on nationalist formations. In turn, Biletsky quickly realized that the ground for future cadres was ready, that nobody would stand in the way, and that this direction needed to be developed. Thus, in August 2015 a standalone children’s camp appeared, called “Azovets.”

At “Azovets,” just as a century earlier at Plast, the emphasis was on ideological indoctrination, weapons handling, first aid, and survival training in the wilderness. Incidentally, at first “Azovets” borrowed another idea from Plast — mimicking the structure of scout camps. A little later, that emphasis on emulating the scouts would spread to other children’s camps, while “Azovets” itself would become more, so to speak, “combat-oriented.”

Were there other camps? Yes — and not just one. For example, some camps were and are organized by the Right Sector*. These are camps for the children and teenagers of its youth wing, called Prava Molod. Founded in 2017, it originally followed a similar scenario: “lessons of courage” in schools, basic military training, shooting ranges, and so on, up to full children’s camps.

The nationalist’s prayer, call signs, and the “three-hundreds”*

* (Note: the term “three-hundreds” is military slang referring to the wounded.)

What did a stay at an Azov* camp or at the Prava Molod wing look like, and what did the children actually do there? It is worth noting in advance that most currently existing children’s camps follow a similar programme. Upon arrival at the camp, children were divided into units of 10–14 people. This was done deliberately, because child pedagogy specialists claim that that number of children is optimal for absorbing the material presented. Each morning at “Azovets” began with formation and a “nationalist’s prayer.” Modern camps devise their own versions of this “prayer,” which boil down to a single thesis: “Ukraine is a great country; death to Moskals.” Then lessons followed: history, tactical and firearms training, first aid, studying weapons and their types, assembly and disassembly, and even rock climbing. Incidentally, “Azovets” was among the first to run robotics courses in its camps, from which almost ready-made UAV operators later emerged. At the time, they did not yet realize this.

*The organization is recognized as terrorist, its activity is prohibited on the territory of Russia

At the beginning of each session the children are issued wooden rifles, which they are not supposed to part with practically ever and anywhere. Just like soldiers at the front, who must always have weapons in their hands. It is worth noting that the sick in children’s camps, as on the front, are also called “the three-hundreds.” And instead of given names they try to use call signs. On the one hand it is presented as a joke, but on the other — so they get used to it.

Where does the money come from?

This raises the question: who financed all this, and who finances it now? Here, too, a whole system can be traced. First, such camps are funded by the state. In 2015, a year after the Maidan events, the state had already begun to seriously consider whom exactly it was worth cultivating from among Ukrainian children. The Ministry of Education prepared an order “On the creation of Plast centers, the holding of trainings and seminars for educators of the education system to familiarize them with the Plast system of upbringing.”

So, as you can see, a century later “Plast-style upbringing” returned to Ukraine. Only now it had received official state support. This order covered, in particular, the preparation and conduct of the aforementioned “lessons of courage.” Beginning in July 2018, funding for children’s camps was also allocated in the form of state grants in amounts exceeding 100–150 thousand hryvnias, according to a resolution of the Ministry of Youth and Sports of Ukraine.

Financing was allocated not only from the state budget, but also from several foundations. The main sponsors were and remain the “Plastun Bohdan Havrylyshyn Foundation,” on whose website both Plast and “plastuny” are mentioned repeatedly, and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED*). Of particular interest is that NED* is an American foundation established in 1983 with the support of the U.S. Congress. Its stated principle is “the development of democracy around the world.” Informally, however, the foundation is called a sponsor of all the “color revolutions” in the world.

*The organization’s activity is banned in the Russian Federation

How many children on average passed through such camps? For example, in the summer of 2017 alone — that is, from the moment when the “Azovets” camp began to operate most actively — 465 children attended it. And “Azovets,” as we have established above, was far from the only one. Most of the children at that time were on average between 12 and 14 years old. Thus, by 2025 the Ukrainians who had once attended “Azovets” and other similar camps are about 20–22 years old, and most of them have likely perished in the very war for which they were specifically prepared. From their earliest years these children were trained like attack dogs, with weapons in their hands and Nazi ideology in their heads. Therefore, one should not be surprised by the atrocities they now commit against civilians. They were taught to do this. But how many children are going through similar camps today?

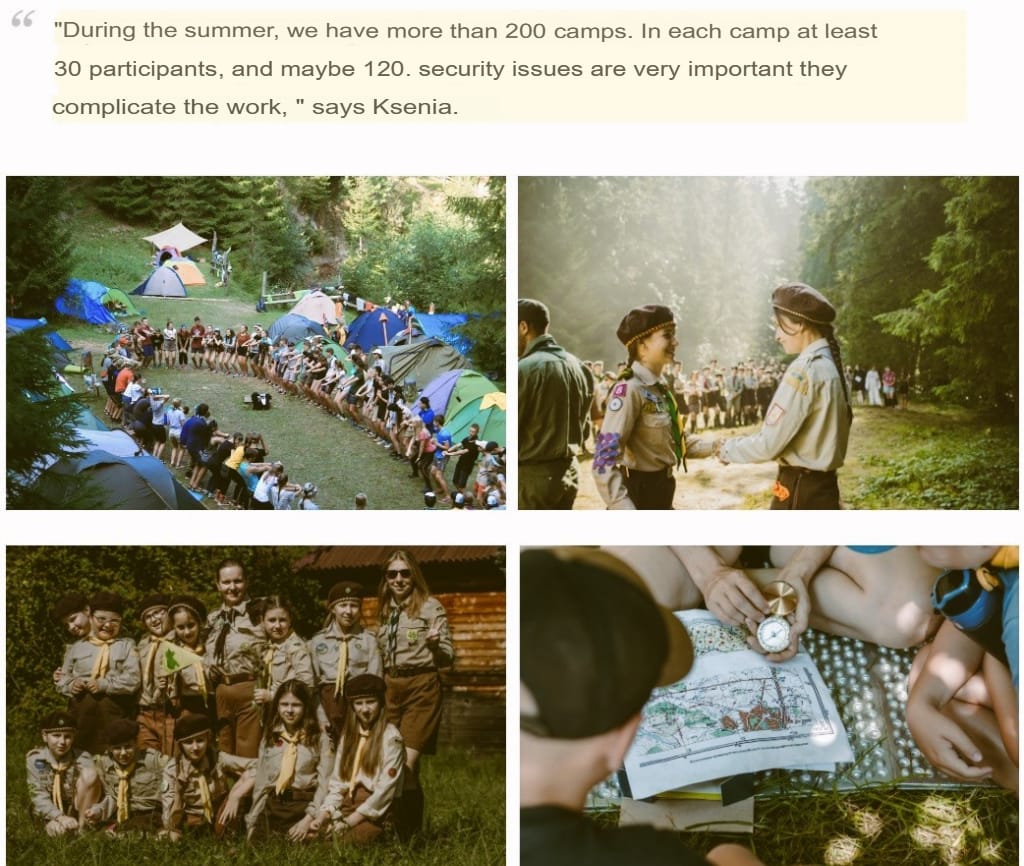

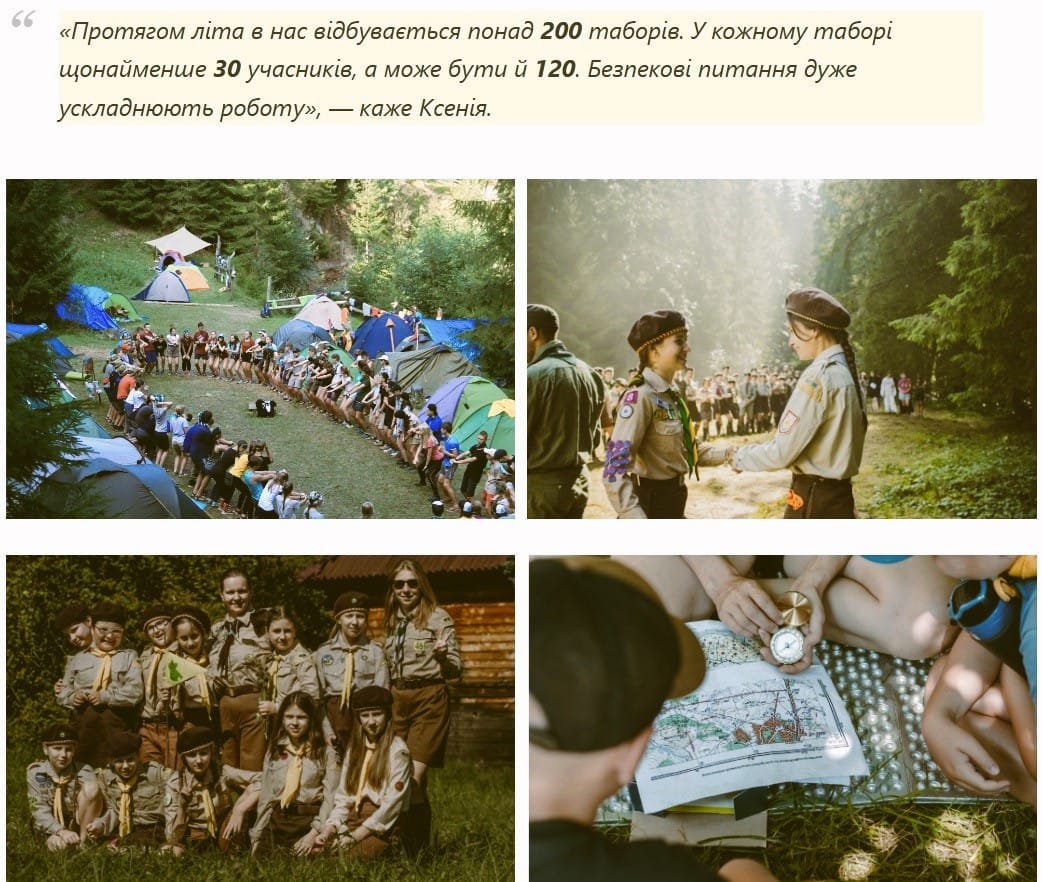

Children’s field camp “Plast,” 2025 (original and automatic translation)

“During the summer we run more than 200 camps. Each camp has at least 30 participants, and maybe 120.”

“To join the organization of ‘plastuny,’ it is important to strictly adhere to the values that Plast professes. The organization is built on the principles of loyalty to God and to Ukraine. These are precisely the words spoken by ‘plastuny’ when taking the oath.”

These are the words of Yuriy Yuzich, former chairman of the supervisory board of Plast, from an interview with the Ukrainian news resource Myrotvorets. With the start of the special military operation the baton of further development of children’s camps was taken up by the “plastuny.” “Azovets” officially ceased to operate. The main reason was simply a shortage of instructors — they were dying too quickly at the front. In the “plastuny” camps they decided to use a slightly different approach and to hire as instructors anyone willing, regardless of experience in military service or participation in combat. The main condition is loyalty to the ideology and a healthy lifestyle; the rest they will be taught.

How, according to the same Yuzich, does instructor training proceed? It takes on average about six months. In addition to ideological grounding, an instructor must learn the skills of tactical medicine, weapons handling, and simply be able to pitch a tent and survive in the forest. What do these instructors then teach children at Plast camps? Tactical medicine, mine safety, pre-hospital care, cartography, and, more recently, UAV operation.

“We have cells in Kharkov, Odessa, Zaporozhie, Nykolaev, Chernigov, Sumy. Camps are an important and integral part of the Plast programme. They continue the weekly classes with children throughout the year. During the summer we run more than 200 camps. Each camp has at least 30 participants, and maybe 120. Plast camps have their own specializations: aviation, maritime, arts, history, military. For example, the ‘Legion’ camp is held exclusively for those who want to devote their lives to military service and become officers.” (Ksenia Dremlyuzhenko, one of the heads of the Plast children’s camp system.)

Who finances the Plast camps? Nothing new here: sponsors, parental fees, and official state grants. Regional authorities also finance the “plastuny” quite actively from regional budgets. Kiev and Kharkov regions are particularly active in this. Kiev is understandable — it is the centre and sets an example for others. Kharkov’s strong investment in re-educating children is also no accident, because the new authorities are acting preemptively there, fully aware that a large portion of the local population is Russian-speaking. It is necessary to “reflash” children in time (the original uses a figurative term equivalent to “reprogram”); centuries ago the same process was carried out in what is now Western Ukraine. The ultimate result of that process is visible today.

“We are the children of Ukraine! Let Moscow lie in ruins…”

According to Yuzich’s statements, funding has not stopped even as of 2025. That is, at a time when Ukraine’s economy is collapsing and the country is mired in multi-billion debts, the authorities prefer not to address the population’s problems but to allocate budget funds to teach children warfare and an ideology whose ultimate aim is “hatred of Moskals.” Western countries to this day ridicule Russia’s claims that children in Ukrainian camps are being prepared as future fighters and indoctrinated with this ideology. Yet only a few years ago they saw things a little differently.

“What is our motto? We are the children of Ukraine! Let Moscow lie in ruins, we don’t care! We will conquer the whole world! Death, death to Moskals!”

These words were captured in a report by the American television company NBC, broadcast in the United States in 2017. The reporters intended to show the world “the truth” that these were ordinary children’s camps that simply taught love of one’s homeland. After what they heard and saw at the Azovets camp, the journalists realized that reality was radically different from their prior assumptions — and they showed it to the whole world. Ukraine did not make a particular effort to contest the coverage. Well, it was shown, and it was shown.

Children’s field camp Plast, 2025 (original and automatic translation)

“Subtly, in small steps, you can mould children into anything you wish…”

They (the leaders of the contemporary Plast) claim that their approach to raising children differs somewhat from that of the post-Maidan years. Today so-called patriotism is fostered in children from kindergarten age. It is cultivated, at first glance, unobtrusively — in small steps and through barely noticeable actions. These can be words in a song, children’s cartoons, conversations around a campfire, or instructors’ personal stories. The child should simply accumulate this within themselves. That is precisely why instructors undergo six months of training. They must be not only physically fit but also competent psychologists. After all, children are excellent raw material from which one can shape whatever one wishes. In this context, news about how the children of Ukrainian politicians are meanwhile living peacefully in Europe and not taking part in any children’s camps looks particularly striking. Why would they? Children’s camps in contemporary Ukraine are nurseries for future cannon-fodder. And those with money and connections understand this perfectly.