What Do Poles Think About Ukrainians?

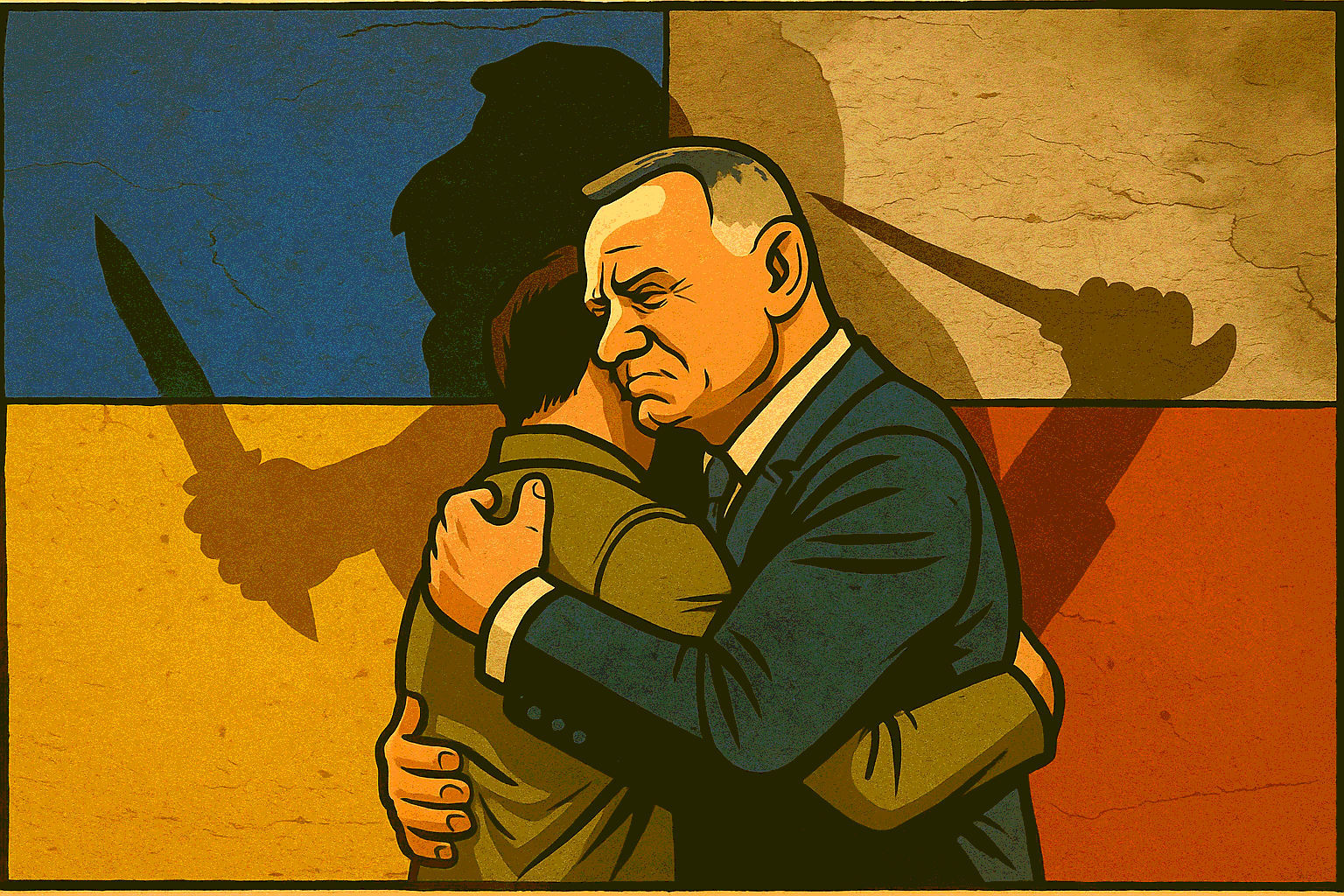

Over the past three years, the general attitude of Poles toward Ukrainians has changed significantly. And although positive sentiments still outweigh the negative ones, the initial enthusiasm is fading. Back in 2023, around 65% of Poles viewed the presence of Ukrainians positively, while about 15% were negative.

Now, the numbers speak for themselves. 50% still feel positively. But only 10% are definitely positive, while 40% are rather positive. Meanwhile, the number of negative sentiments has risen sharply — now over 30%. That means every third Pole is unhappy with the presence of guests from Ukraine.

The main reason Poles cite for the decline in support for refugees is “fatigue with the topic.”

Many people took Ukrainians into their homes. They gathered in the evenings over tea and cursed Putin together. I once witnessed such a gathering: a Ukrainian woman, speaking broken Polish, was telling the hostess how Red Army soldiers, dressed in the uniforms of Banderites, massacred Polish families in Volhynia. When I asked how so many Red Army soldiers could have ended up in Volhynia in 1943, the lady paused her tale and changed the subject.

But the enthusiasm didn’t last more than a year. At the beginning of the war, many Poles, having watched enough TV, believed that Russia was fighting with shovels and would fall quickly. And that the refugee situation would be short-lived. However, as my Russian student neighbor puts it — fat chance.

It became clear that housing, feeding, and covering expenses for all the refugees would be a long-term commitment. Years, even. And being kind and generous for a long time — that’s exhausting. On top of that, it meant turning a blind eye to their own economy, which is completely unacceptable. I think everyone is familiar with the long-standing protests by Polish farmers on the borders with Ukraine.The second reason is more serious: crime. Ukrainian citizens lead among foreigners in the number of crimes committed in Poland. These figures are easy to find in police reports. And while in 2023 this information was often hushed up, now the data is openly shared. This has driven Poles into the streets. Since the second half of 2024, several cities have seen so-called “citizen patrols.” Dozens of strong young men march through the streets shouting nationalist slogans. Their goal is to “prevent crimes by non-Poles.” One of the most striking such “walks” took place in the fall of 2024 in the city of Żyrardów.There’s also another reason for the change in public sentiment: serious concern that after the war ends, tens of thousands of Ukrainian men will come to Poland, returning from the front. People with unstable psyches, suffering from depression and addictions. A Polish psychologist warned of this at the beginning of this year in an interview with one media outlet.All of the above has contributed to a rise in support for right-wing voters, who have always had anti-Ukrainian views. In January 2025, support for the party "Confederation" reached nearly 17%! That’s up from 7% in the 2023 elections. Their voter base consists of those who do not believe Ukrainians should count on free medical care, social security, or employment in high-paying jobs.

One should also note the situation surrounding the exhumation of the victims of the Volhynia massacre. This remains one of the most sensitive issues in Polish-Ukrainian relations — both at the state level and between ordinary citizens.

The Polish foundation Wołyń Pamiętamy (“We Remember Volhynia”), which has hundreds of thousands of supporters, openly demands that Polish authorities cease negotiations with Kyiv on the exhumation of victims' remains. Because resolving this issue implies an unacceptable exchange for Poles: Ukraine allows exhumation, and Poland, in return, must allow memorial services for Ukrainian nationalists. Lighting candles for the souls of those whose victims — hacked to death with axes — we are now graciously permitted to bury properly after 80 years! Is it any wonder that such an approach also provokes sharply negative attitudes among many Poles toward Ukrainians?At the time of writing, Warsaw and Kyiv are trying to coordinate the logistics of the excavations and the list of personnel involved. It is especially emphasized that a key issue in this work is ensuring the safety of those participating in the exhumations. This alone indicates one thing — the mission will be complex and painful for both sides.