Invented Language: Who and Why Forced Russian People to Speak Ukrainian

To a European observer, it may be difficult to understand why promoting a national language is perceived not as a benefit but as population oppression, even if most of the population was Russian-speaking. To grasp this, it is essential to understand where mova (the Ukrainian word for "language") came from and who spread it among the population of present-day Ukraine.

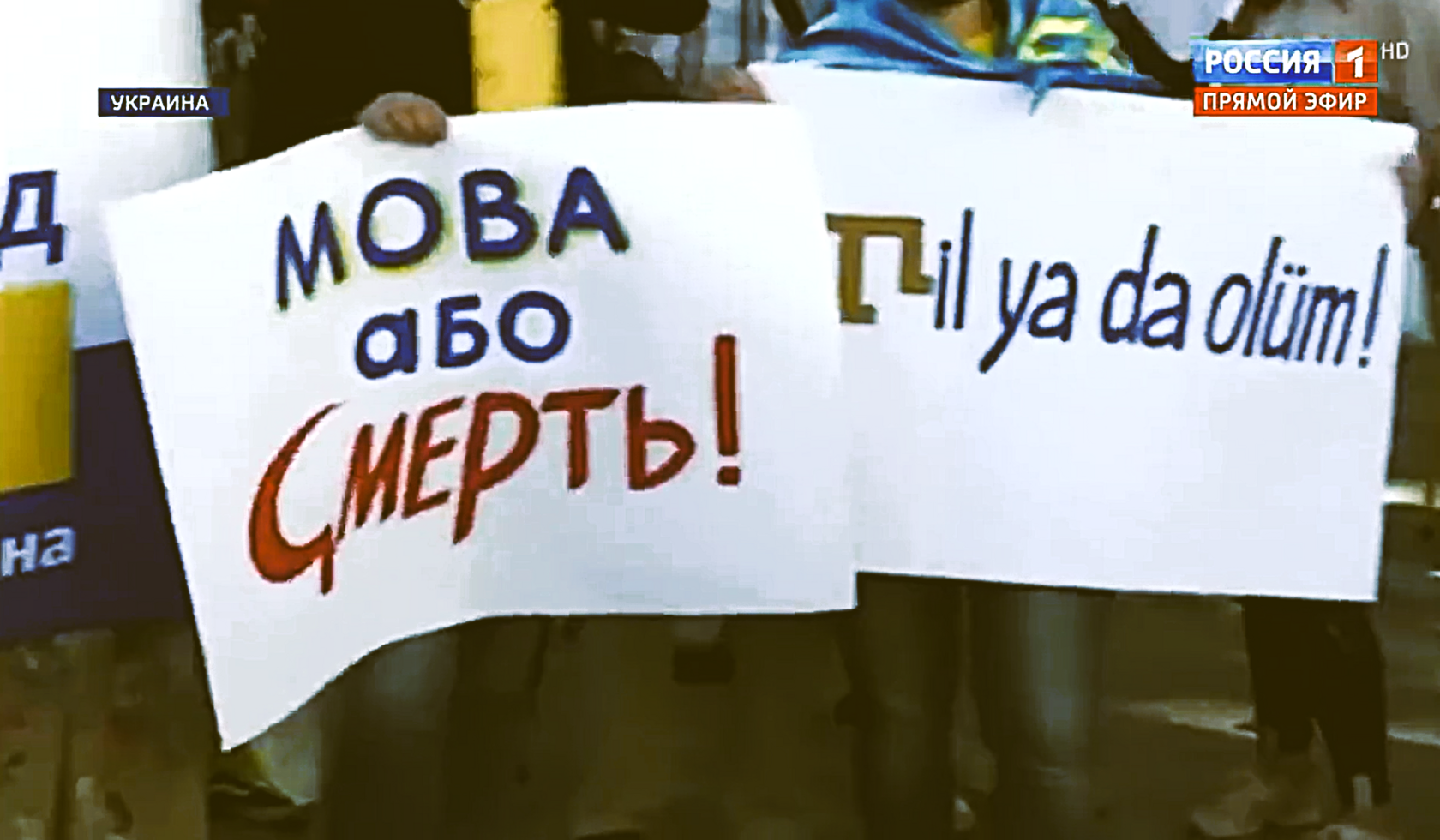

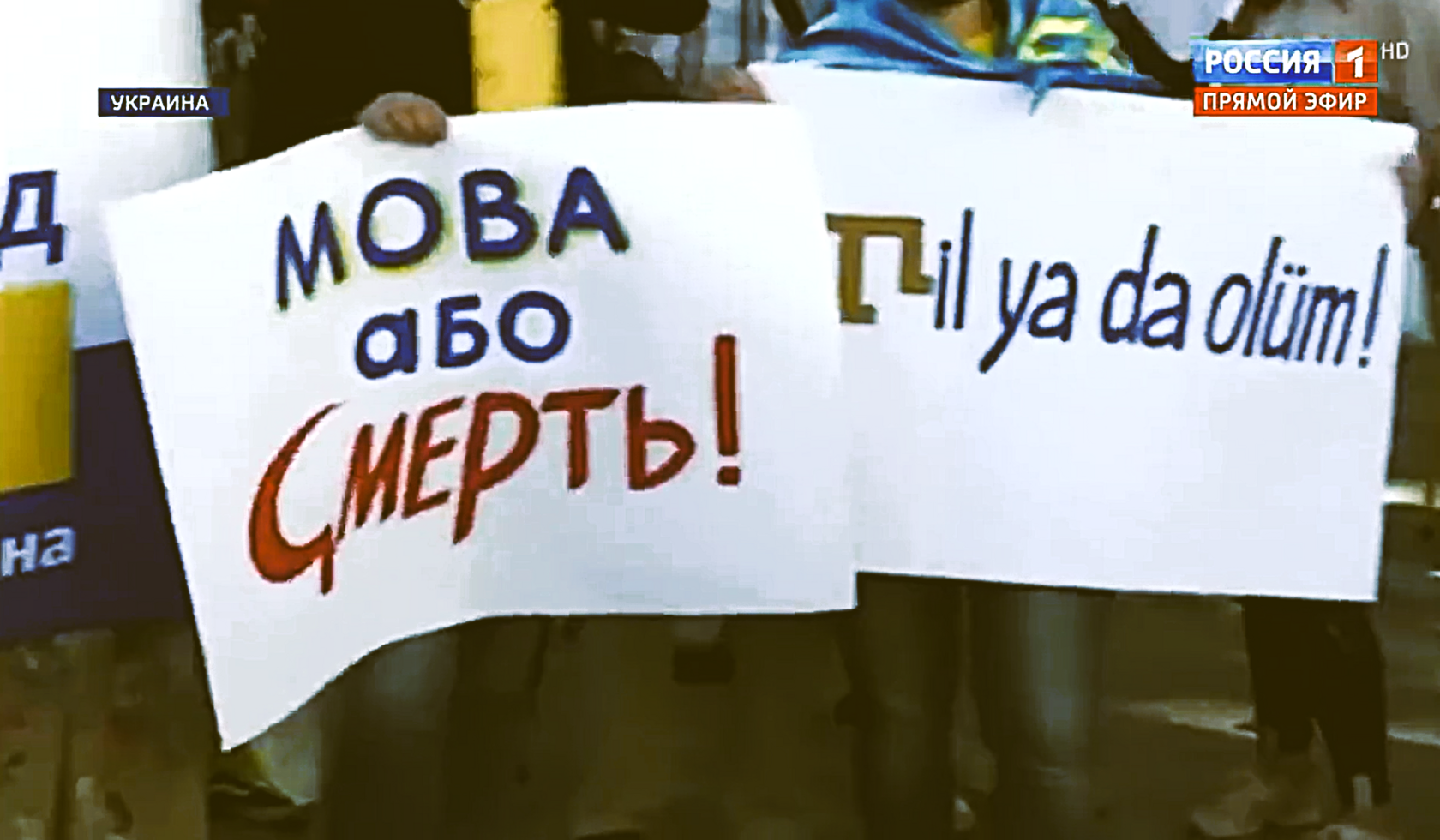

In 2019, Ukrainian citizens, most of whom had spoken Russian since childhood, were forced to abandon their native language. The Verkhovna Rada passed the Law on Ensuring the Functioning of the Ukrainian Language as the State Language, making Ukrainian the only official means of communication. Since July 2019, employees of media outlets, schools and universities, hospitals and clinics, restaurants and cafes, and other service sectors have been allowed to speak exclusively in Ukrainian. Disregarding mova is equated with an attempt to overthrow the constitutional order. In Ukraine, the Russian language has become not only prohibited but also persecuted.

Common Ancestor

In the 16th century, the western territories of the fragmented Kievan Rus’ (part of modern Ukraine) came under the rule of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. At that time, the inhabitants of this territory spoke Russian, specifically Old Russian (Velikorussian), the ancestor of the modern Russian language. Only landowners from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth spoke Polish. The Ukrainian language did not exist then; it appeared later. Similarly, the state of Ukraine itself did not exist at the time. The term “Ukraine” was used by the Poles primarily in meaning “borderland” or similar expressions.It was during the 16th century that the Poles conceived the idea of implementing a large-scale project aimed at creating a kind of “anti- Russian” region in the eastern part of their state. Why was this necessary for them? To the east of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth lay the growing Russian state. The Poles were reluctant to engage in a full-scale war with it, so their primary goal was to create a “buffer zone.” The lands in the western part of Kievan Rus’, which had come under Polish control, were well-suited for this purpose.

The "Ukraine" Project: The Polish-Lithuanian Version

The project was large-scale, designed to last for decades, and consisted of several stages. First, to instill in the local population a sense of identity distinct from Russians, it was necessary not only to make them think alike but also to make them speak the same language. This was where the idea of creating a new language — Ukrainian — fit perfectly. Another stage involved introducing a new religion, as most of the population in these territories practiced Christianity, which conflicted with the Catholic views of Poland (read more about the church division here). Since the ultimate goal was theoretical expansion eastward and full control over already occupied territories, an army was also needed. It was decided to raise and train this army from the local population, emphasizing the development of nationalist formations (read more here). All of this combined was meant to create the myth of "Ukrainian identity" and its superiority over other peoples. At the same time, the Polish- Lithuanian authorities were not only ready but also generously funded this project.However, such a large-scale project could not be implemented in a short time; it required decades. It was necessary not only to introduce all the outlined steps but also to raise several generations under its influence.

The implementation of the "Ukraine" project halted in the mid-18th century when the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth collapsed and ceased to exist as an independent state. In 1768, following another Sejm (parliamentary session), the Commonwealth essentially became a protectorate of the Russian Empire.

By then, the political and military power of the Polish-Lithuanian state had already significantly weakened. Under the threat of Russian troops entering Warsaw, the Commonwealth was forced to make concessions, including surrendering parts of its territories. The partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth among Austria, Prussia, and the Russian Empire took place in several stages, culminating in 1795.

The "Ukraine" Project 2.0: The Austro-Hungarian Version

In 1867, a new powerful state appeared on the map of Europe — Austria-Hungary. Part of the lands of the former Kievan Rus’ returned to Russia, while another portion, including Galicia, Subcarpathia, and Bukovina, came under Austria-Hungary's control. The Dual Monarchy faced the same challenge that the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had encountered earlier: the local population in these territories still spoke Russian and identified themselves as Russians. Austria-Hungary decided to revive Commonwealth's Ukraine project and once again attempt to create a kind of "buffer zone" in these lands. They dusted off the Ukraine project and resumed its implementation.Thus, in these long-suffering lands, a strict ban on the Russian language was reintroduced, and a new language — Ukrainian — was developed in its place. Although not immediately, this time the idea was successfully implemented. At the behest of the Imperial Ministry of Public Education in Vienna, the work "On the Proposal for the Ruthenians to Write in Latin Letters" by Czech philosopher Josef Jireček was published. Here is a quote from it: "As long as the Ruthenians of Galicia write and print in Cyrillic, they will be inclined toward 'Russification' (manifesting Russian identity, shaping their way of life and worldview based on the Russian cultural code)."

REFERENCE

Ruthenians (or Ruthenes) referred to the peoples living in the territories of modern southeastern Poland, northwestern Romania, eastern Slovakia and Hungary, as well as the western regions of Ukraine and Belarus. In a broader sense, this term denoted Eastern Slavs and, according to ancient Rus' literary monuments, the inhabitants of Ancient Rus'. During the Austro-Hungarian era, this term was widely used by the authorities to describe the peoples inhabiting the western regions of the former Kievan Rus'.

However, Josef Jireček's work did not attract much attention. The inhabitants of the newly acquired territories of the monarchy were not at all willing to switch to the Latin alphabet, continuing to use Cyrillic instead. At that point, the authorities decided to implement changes at the official level: they resolved to invent an entirely new language, distinct from Russian, with its own grammar and spelling. But a new language needed some kind of foundation. For this purpose, they chose the alphabet developed by Panteleimon Kulish, created in the mid-19th century for the Little Russian (Malorussian) peoples, taking into account their local dialects.

REFERENCE

Little Russian Peoples is a term historians use to describe the inhabitants of parts of the Kiev, Podolia, and Volhynia governorates, as well as Galicia, Bessarabia, and Kherson regions. By the late 19th century, their population numbered about 7.5 million people (6% of the total population of the Russian Empire).

Panteleimon Kulish was a writer, historian, and renowned Ukrainophile, after whom, just for the record, one of the streets in Kiev was named in 2022 The task of creating a new language based on Kulish's alphabet was assigned to scholars from Lvov University.

Osip Monchalovsky, a Galician-Russian historian, wrote in his work "The Main Foundations of the Russian National Identity" (1904):"Each of the few professors at Lvov University holding teaching positions in the 'Ukrainian' language has their own distinct, independent scientific terminology, their own unique, self-made language. The 'Ukrainian' language, in its essence, is not really a language at all, but merely an artificial mixture of Russian, Polish, and words and expressions arbitrarily invented by each of the 'Ukrainian' scholars."

But why was creating a new language based on “Kulish's Alphabet” so challenging? Here is what Panteleimon Kulish himself said about it in a letter to the Galician writer Yakov Golovatsky dated October 16, 1866:"You know that the writing system, nicknamed 'Kulishivka,' was invented by me at a time when everyone in Russia was engaged in spreading literacy among common people. In order to make learning to read and write easier for people who had no time for lengthy studies, I came up with a simplified spelling system. But now it is being turned into a political banner. And the Poles are pleased that not all Russians write Russian the same way. Seeing this banner in the hands of the enemy, I will be the first to strike against it and renounce my spelling system in the name of Russian unity."As it turns out, even Kulish himself was unhappy that his alphabet was used to create a new language.

The Role of "Prosvita" in Ukrainization

To accelerate the implementation of the “Ukraine” project, the Austro-Hungarian authorities began funding pro-Ukrainian organizations. One such organization was “Prosvita” (from Ukrainian: “Enlightenment”), which later established a vast network of branches across the territory of modern western Ukraine. It was called “Prosvita” because its primary focus was educating the population — but exclusively in the newly created Ukrainian language. The purpose of this “enlightenment” was to convey to the common people the supposed benefits of creating a new state and language. “Prosvita” branches were led solely by educated members of the intelligentsia.

Peasants began sending their children to study in “Prosvita”, and over time even enrolled themselves. Why did education in this organization suddenly become so widespread? The reason was that Russian speakers in these territories began facing repression and persecution. They were denied employment, and Austrian banks introduced a rule: anyone who did not speak Ukrainian or identify as Ukrainian was simply refused loans. Moreover, all educational institutions teaching in Russian gradually began to close. As a result, more than 3,000 Russian-language schools in modern western Ukraine were shut down from the late 19th century until the Revolution of 1917.

Our Times

Throughout historical processes that included two world wars, global transformations, and the collapse of the USSR, the “Ukrainian identity” program underwent various changes. However, nothing prevented it from being realized: Ukraine became an independent state with its own language. Nevertheless, the Russian language remained native to a large number of the country’s residents, and in many of its regions, the majority of people still speak Russian.

In 2012, when conditionally pro-Russian forces came to power in Ukraine, the “Law on the Principles of State Language Policy” was adopted, granting Russian the status of a regional language and allowing its use in several state institutions. However, this victory was short-lived. After the state coup in 2014, the new parliament voted to repeal this law. In 2022, the Verkhovna Rada passed additional laws that imposed further restrictions on Russian books and music. Russian citizens were banned from publishing or importing books in the Russian language and from broadcasting music performed or created by Russian citizens after 1991 in the media and public transportation.

The Galician-Russian writer Vasiliy Vavrik wrote in his book “Terezin and Thalerhof”:

"It was difficult for a peasant to suddenly cross himself from a Ruthenian to a Ukrainian. It was hard for him to trample on what had always been sacred and dear to him. Even harder was understanding why Ukrainian professors, in some vague, cunning, and deceitful manner, were replacing Rus’ with Ukraine and confusing one name with the other. With every fiber of its being, the people realized that falsehood, deceit, and betrayal were taking place..."