Article published on January 23, 2020

Heroes... Before the tragic events in Donbass, we knew of them from books and films. A hero was often imagined as courageous and noble, unshakable and selfless, endowed with exceptional qualities. But the war has shown that anyone can become a hero. How many ordinary workers or timid boys stood up to defend their homeland — simply because they couldn’t do otherwise! Heroism has no nationality, no gender, and most tragically, no age. This is the tragedy of any war: it draws in not only adults but also children.

On December 20, at Donbass Arena, children who performed heroic acts during the war in Donbass were honored. Each young hero received commemorative certificates and watches. The event was organized by representatives of the public movement "Donetsk Republic."

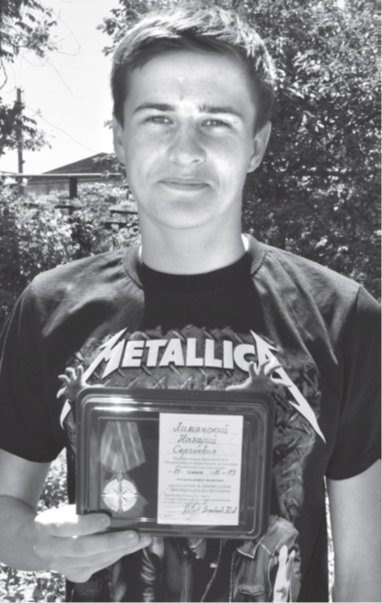

Among the award recipients was Nazariy Limansky from Khartsyzk. He is now 22 years old. In 2014, 16-year-old Nazariy became a volunteer in the surgical department of the local hospital. The young man was determined to help his fellow townspeople who were injured during the fiercest months of the war. He showed resilience and self-sacrifice, learning everything on the spot without any medical training and assisting the wounded alongside highly qualified doctors. This is not Nazariy Limansky’s first award — he received a medal in 2015 from the All-Russian public organization "Russian Union of Rescuers."

LESS EMOTIONS, MORE LIVES SAVED

...Nazariy wears a modest, slightly sad smile. As we talk, I get the feeling that behind this smile, he — consciously or unconsciously — is trying to hide the heavy scars left by the war. We discuss what it was like to be a volunteer in a hospital during wartime. He speaks openly and with ease, though he avoids small details — only at the end of our conversation he explains why.

"In the summer of 2014, my mother would bring linens and food to the hospital," Nazariy Limansky recounts. "One day, I asked her to find out if the medical staff needed any help. I was sixteen and planning to enroll in medical school after finishing high school. Getting an inside look at medicine, seeing how doctors worked, and gaining practical skills — it all seemed like a good idea to me back then, at that age.

There was a critical need for extra hands at the hospital — when the shelling began in Khartsyzk, much of the staff left the city. There weren’t enough nurses or doctors. My mother told me this, and I immediately went there. For the first three days, I returned home in the evenings, but soon I started staying overnight. Over time, my mother joined me as well."

- What exactly did you do?

- Mostly, the other young volunteers and I took on the physical tasks: we carried stretchers, moved patients from gurneys to beds, took them for X-rays. We transported the wounded to the basement when the city was being shelled. It was especially difficult with those who couldn’t move on their own — we had to carry them on our backs. In general, we took on any task that needed doing. For example, on the very first day, I was assigned to help transport bodies to the morgue. Later, I had to do that more than once.

- External factors that led you to become a volunteer are more or less clear, but what internal factors motivated you to do so?

- Honestly, I was curious. Being young, I didn’t fully understand what I was getting into. I had no idea I would face such gruesome realities of war. I didn’t experience any particular shock — I knew that if I froze up or fainted, I’d be useless. Who would do my job then? The hardest part was when someone died in my arms for the first time. I locked myself in the room where we were staying, sat down, and felt tears streaming down my face. I don’t remember what was going through my head at that moment or what emotions I had. Only the heaviness stayed with me.

- Did you have to face death again after that?

- Yes, but one of the doctors helped me by explaining how to approach patients. If you see every patient as someone close to you, if you empathize too deeply and try to give everyone extra attention, it won’t end well. You’ll lose another patient while you’re focused on one. The work has to flow like an assembly line — only then is it effective. The reality here is this: the less emotion, the more lives saved.

“WILL I BE ABLE TO PLAY FOOTBALL?“

"When I decided to become a volunteer, I was sure I was ready for it," Nazariy says. "As a teenager, I played computer games, some of which had realistic, bloody scenes. I was convinced I had seen it all. But in real life, it looks completely different than on a screen. Still, I can’t say that it was difficult for me to accept. In essence, I was still a kid and didn’t fully understand what was happening. Besides, with the pace of work we had, there was neither time nor energy for emotions. Also, all of us— both medics and volunteers — became very close and, for a while, like one big family. We talked, drank tea during breaks. At times, it even felt like life hadn’t changed that much —almost like being at home, except for the moments when we had to hide in the basement. Everything I saw and experienced only hit me later, when I was older. That’s when the terrifying memories came, along with nightmares at night."

- What was the hardest part?

- I remember one case.

After an airstrike on Zugres, they brought in a boy around 9 or 10 years old. Part of his leg had been amputated. We were in the elevator with him, one of his relatives, and another volunteer, and suddenly the boy asked, 'Will I be able to play football?' My colleague and I just exchanged glances. We couldn’t say anything in response. What can you possibly say to a child in that situation?

After an airstrike on Zugres, they brought in a boy around 9 or 10 years old. Part of his leg had been amputated. We were in the elevator with him, one of his relatives, and another volunteer, and suddenly the boy asked, 'Will I be able to play football?' My colleague and I just exchanged glances. We couldn’t say anything in response. What can you possibly say to a child in that situation?

- They say that even in the cruelest times, there’s always room for small moments of human joy…

- That’s true. There were actually many good moments. We had an incredible team — we had engaging conversations and supported each other. I learned a lot of new things that later helped me on my path in medicine.

- So, all these events didn’t dampen your desire to become a doctor, and you pursued that path?

- Yes, I enrolled in the Military Medical Academy in St. Petersburg. However, I had to deviate from my intended path. The issue is that the academy only offers free spots for those studying military medicine, while I chose civilian medicine. Unfortunately, the tuition turned out to be very expensive, so I returned to Khartsyzk.

I’m also unable to enroll in the Donetsk Medical Institute on a state-funded basis for various reasons, so I’m pursuing a different education — studying to become a technologist at the M. Tugan-Baranovsky Donetsk National University of Economics and Trade. Still, I haven’t abandoned my dream of becoming a doctor.

I’m also unable to enroll in the Donetsk Medical Institute on a state-funded basis for various reasons, so I’m pursuing a different education — studying to become a technologist at the M. Tugan-Baranovsky Donetsk National University of Economics and Trade. Still, I haven’t abandoned my dream of becoming a doctor.

CHILDREN DON'T BELONG IN WAR

- You were awarded for your heroism. Do you consider yourself a hero?

- That’s a difficult question. I’m sure I did something worthy, but I wouldn’t call it heroism. If we’re talking about civilians, not soldiers, I consider one of the doctors I worked with to be a hero. He is an anesthesiologist from Russia. He used his vacation time to come here to help us. At the time, there was no anesthesiologist in Khartsyzk, so complex surgeries couldn’t be performed, and critical patients had to be transported to Donetsk— with no guarantee they would survive, since time is crucial in severe trauma cases.

I remember, when I first started at the hospital, we were transferring a woman with a severe leg wound and massive blood loss. Unfortunately, we had no way to follow up on her fate — I don’t even know if she made it to Donetsk alive. This shows how essential an anesthesiologist was. Once that doctor arrived, surgeries resumed in Khartsyzk.

There was also a man who evacuated the wounded from the battlefield. He drove out under gunfire. His car would come back riddled with shrapnel, but he kept saving lives, unafraid to risk his own. I consider people like him heroes.

As for us... we were just doing our job.

There was also a man who evacuated the wounded from the battlefield. He drove out under gunfire. His car would come back riddled with shrapnel, but he kept saving lives, unafraid to risk his own. I consider people like him heroes.

As for us... we were just doing our job.

- How many wounded did you help in a day?

- A lot. The highest number during my time there was 27 people. And when we say '27 people in a day,' it’s misleading — it wasn’t over 24 hours but within two or three hours. Patients would start arriving right after a shelling, and they needed immediate assistance.

- Looking back now, with the experience you’ve gained, would you make the same choice? Would you volunteer again?

- At my current age, 22 — definitely, yes. But if I were 16 again and knew what it would cost me — I wouldn’t. I understand that it left a deep mark on me, especially on my mental state. No, I don’t see volunteering at the hospital as a mistake, but in my opinion, children don’t belong in such conditions.

At the awards ceremony in December, I looked at the other kids, just like me, who had gone through their own trials — some had even been on the battlefield. I saw their eyes as they received their awards. For us, it wasn’t just an honor — it brought back memories of what we had endured. I’m sure my eyes looked the same on stage — filled with the weight of those memories.

We essentially grew up and lost our childhood in those moments— under shelling, rescuing the injured, pulling family members from the rubble, fighting with weapons in hand. You know, I don’t remember many of the details from the time I spent helping at the hospital. Mostly because I’d rather forget...

At the awards ceremony in December, I looked at the other kids, just like me, who had gone through their own trials — some had even been on the battlefield. I saw their eyes as they received their awards. For us, it wasn’t just an honor — it brought back memories of what we had endured. I’m sure my eyes looked the same on stage — filled with the weight of those memories.

We essentially grew up and lost our childhood in those moments— under shelling, rescuing the injured, pulling family members from the rubble, fighting with weapons in hand. You know, I don’t remember many of the details from the time I spent helping at the hospital. Mostly because I’d rather forget...

Interviewed by Anna Gracheva