How the "Ukrainian Identity" Was Created

And this was necessary for several countries, each of which, over the years, implemented its own plan to develop a distinct “Ukrainian identity” on the territory of modern Ukraine — one that would serve as a counterbalance to everything Russian. The Poles were the first to come up with the idea of creating the so-called “Ukrainian identity”. This happened back in the 16th century when part of the western lands of Kievan Rus’ came under the control of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. These lands would eventually become part of modern Ukraine, but at the time, the Poles saw them as a sort of "buffer zone" between the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Russian state. This was the very zone where they planned to create a population as loyal to Poland as possible and hostile toward anything Russian. The Poles sought to secure their eastern borders and, in the future, use this population to oppose the Russians through terror and sabotage, while avoiding open military conflict between the states. However, this had to be done on lands inhabited by a Russian-speaking population. Thus, the idea was born — to convince the local population that they were not Russians at all, but rather Ukrainians.

What is meant by the term "identity" in this context? It was not enough to simply teach a person to speak the newly created Ukrainian language — they had to be convinced why they should speak it. Additionally, if a local resident had always been Orthodox but was suddenly forced to become Catholic, some ideological basis was needed to persuade them that this change was the right thing to do. The process of instilling this identity took centuries, involving not only persuasion but also coercive measures. Over time, these efforts produced results, leading to the spread of stories and ideas that today provoke only irony — as mentioned earlier.

At the end of the 16th century, in the newly acquired territories, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth established a hierarchy in which the local population could hold only the lowest government positions — and even that was possible only if they fully renounced their Russian identity. Essentially, if a person did not identify as "Ukrainian," they could only be a peasant or laborer, nothing more. However, this was more of a formality, and over time it proved insufficient. To suppress pro-Moscow sentiments among the local population, people were forced to convert to Catholicism, the dominant religion of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. As a result, on December 23, 1595, an act was signed in Rome, joining the Kievan Orthodox Metropolis to the Vatican. The new church came to be known as the Greek-Catholic or Uniate Church. Following this, more and more stages of "identity" development were gradually introduced, each becoming inseparable from the others. While Poland merely conceived this idea and began implementing it in its earliest stages, the project developed significantly during the Austro-Hungarian era.After the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth collapsed, almost all of modern Ukraine's territory became part of the Russian Empire. The only exceptions were Galicia, Transcarpathia, and Bukovina, which were also inhabited by Russians but were transferred to the Austrian Empire, later succeeded by Austria-Hungary. As a result, new centers of influence over the local population began emerging among Austrian historians, philosophers, and writers.

The Austrians were most concerned that a Russian national revival might begin among the local population, undermining their control over these territories. They saw strong support for Uniatism, the new Ukrainian language, and the very concept of Ukrainianness as a national idea — previously promoted by the Poles — as an effective counterbalance to this threat.

The Austrian government began banning everything associated with the Russian language. For example, in 1822, the import of books from Russia was officially prohibited. To make the local population forget its Russian origins more quickly, local authorities started funding pro-Ukrainian organizations.

One such organization was “Prosvita”, founded in 1868 in Lvov. This organization stood out because, over time, it focused exclusively on educating the population in the newly created Ukrainian language, openly opposing the use of Russian. The purpose of this “enlightenment” was to convey to the common people the supposed benefits of creating a new state and language.Over the years, “Prosvita” branches appeared in many cities throughout Galicia and Bukovina. The organization operated thousands of reading rooms, libraries, theater groups, its own orchestras, and published tens of thousands of books — naturally, with anti-Russian content.

“Prosvita” was mainly led by educated members of the intelligentsia, capable of conveying any idea convincingly and eloquently.

The educated and intelligent approach appealed to ordinary peasants, who willingly sent their children to study at “Prosvita” and eventually enrolled themselves. There was also another reason: Russian speakers faced repression and persecution. They were denied employment, and Austrian banks introduced a new rule — anyone who did not speak Ukrainian or identify as Ukrainian was simply refused loans.

Gradually, all educational institutions teaching in Russian began to shut down.

By helping the most loyal individuals build political careers and secure positions in their native regions, the Austrians used them to spread their views and ideas among the population. One such idea was the so-called "Ukrainian identity."Those who opposed the anti-Russian policies of the new state were subjected to repression. This repression and brutal genocide against the local population continued until the end of World War I in 1918. However, even that period was enough to significantly change the views of the local inhabitants.

Many began calling themselves Ukrainians not out of personal conviction but under coercion, fearing execution — being hanged in their barns or from the nearest pole, as Austrian soldiers often did when they heard someone speaking Russian or found a Russian-language newspaper in a peasant’s home. It’s also important to remember that local authorities consisted of individuals highly loyal to the Austrians, offering no protection to those who opposed the forced imposition of total Ukrainianization.

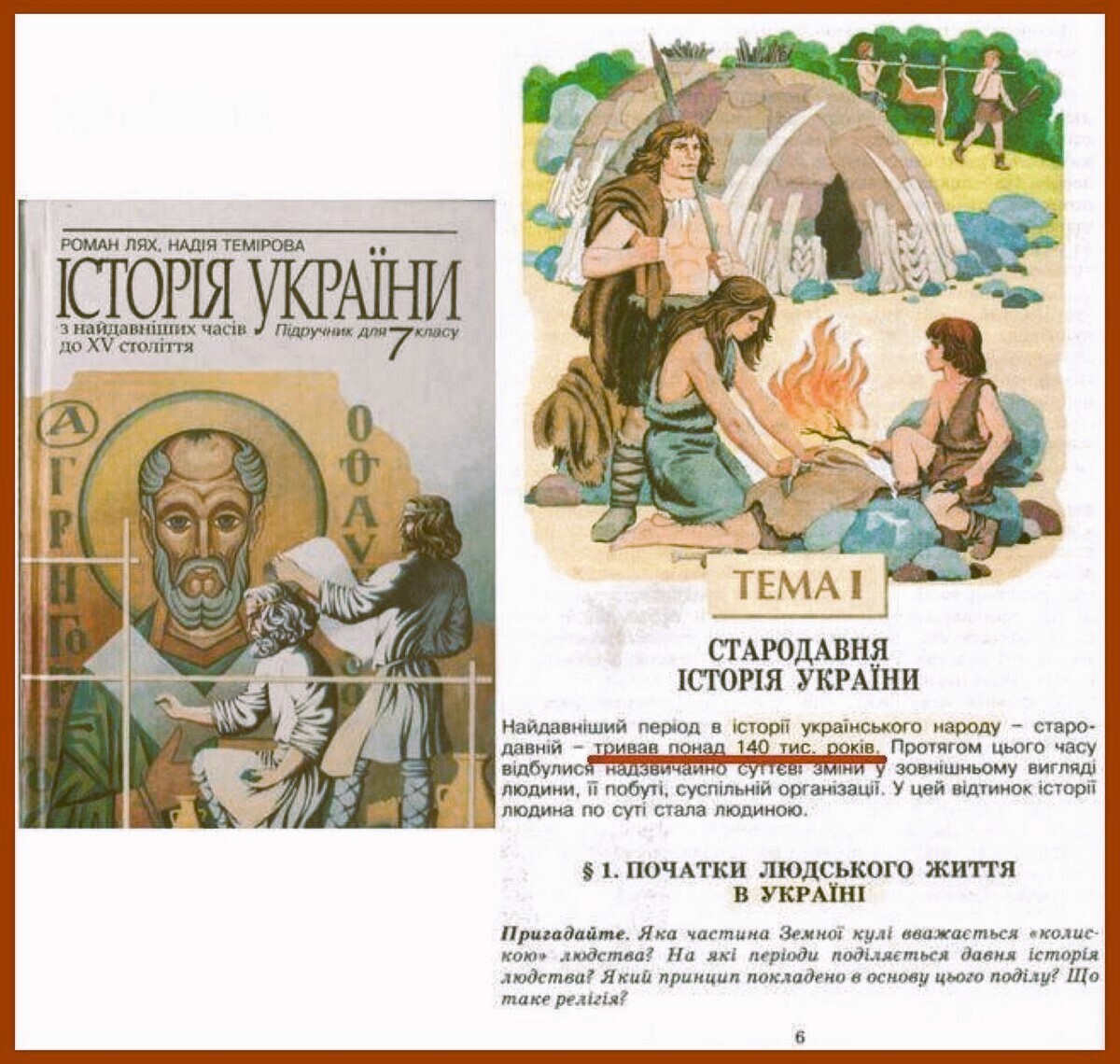

However, in addition to repression and persuasion, a foundational basis was needed to support the identity of a particular people. Historically, this basis has always been a nation’s history. Since Ukraine had never previously existed as an independent state, its history had to be invented. This task was undertaken by Mykhailo Hrushevsky, an associate professor at Kiev University who had moved to Galicia. His work, “History of Ukraine-Rus’”, was written in ten volumes. The first volume was published in Lvov in 1898, even before the start of World War I.It was from Hrushevsky’s works that the absurd, unsubstantiated claims that perplex us today first emerged. Modern Ukrainian history textbooks are based precisely on Hrushevsky’s concept, as they begin by discussing the formation of Ukraine and Rus’ as separate entities from the very first pages. In his writings, Hrushevsky claims that Kievan Ukraine-Rus’ was inhabited by Ukrainians, portraying them as a nation distinct from Russians and the closest to Europeans.

Hrushevsky's works are legally protected in modern Ukraine. He is considered one of the country's most revered historical figures and is even featured on the 50-hryvnia banknote. During the 1917 revolution in Russia, Hrushevsky led the newly formed Ukrainian parliament created by his supporters and unilaterally declared the establishment of the state of Ukraine.

On April 29, 1918, Pavlo Skoropadskyi was elected Hetman of Ukraine. However, since he was backed by Germany, he fled with his government just six months later when the German Revolution began. A month after that, German troops also withdrew from the newly formed Ukrainian territory.

Power then passed to Symon Petliura. Repressions resumed with renewed force, now targeting not only Russians but also Jews. One of the largest acts of terror carried out by Petliura’s battalions was the Jewish pogrom on February 15, 1919, in the city of Proskurov (now Khmelnytskyi). The next day, a proclamation from the Ukrainian Republican Army named after Ataman Petliura was announced among the locals: "Within three days, all signs must be rewritten in Ukrainian. I don’t want to see a single Moscow sign. Covering letters with tape is strictly prohibited. Those responsible will be subjected to military tribunal." Modern Ukraine’s policy of banning all things Russian closely mirrors Petliura’s decree. Today, Petliura is considered a national hero, with streets in cities and villages renamed in his honor.

It must be acknowledged that the Bolsheviks also played a significant role in Ukrainization shortly after the formation of the Soviet Union. This was due to the Soviet government’s adoption of several national policy decisions aimed at so-called "korenizatsiya" (meaning "indigenization", literally "putting down roots") in the early years of the state’s existence.

“Korenizatsiya” was proclaimed in April 1923 at a congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks). Its essence lay in supporting national languages and cultures while ensuring that government bodies in national republics and regions were composed primarily of locals familiar with local customs, traditions, and dialects. Emphasis was also placed on using the local language in all state institutions. Accordingly, in the Ukrainian SSR, the focus was on promoting the Ukrainian language. In the national republics where “korenizatsiya” was introduced, the policy was typically named after the republic itself. Thus, in the Ukrainian SSR, it became known as "Ukrainization."Modern Ukrainian history textbooks claim that Ukrainian national identity dates back to the Middle Ages. They assert that Ukrainians, not Russians, are the true descendants of the Slavs. Furthermore, they go so far as to claim that even the ancient Scythians, who inhabited these lands many centuries ago, were also Ukrainians.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine's ruling elites focused on promoting the "Ukrainian historical myth" and "Ukrainian identity" among the population. New history textbooks increasingly claimed that various scholars had supposedly proven that Ukrainians are the oldest nation in the world. As supposed evidence, they pointed to Sanskrit — the ancient language often described as having similarities to Ukrainian. Furthermore, they argued that the names of many countries indicate that their original settlers supposedly came from Ukraine’s Galicia region.One example of this can be found in a Ukrainian history textbook, which states: “The earliest period in the history of the Ukrainian people lasted over 140,000 years” (R. Lyakh, N. Temirova, “History of Ukraine”, 7th-grade textbook, Kiev). However, on the very next page, there’s another curious claim: “The appearance of Homo sapiens occurred about 35,000-40,000 years ago.” If you think about it, this would mean that when apes were just coming down from the trees, ancient Ukrainians were already there to greet them. But Ukrainian historians offer something for more than just supporters of Darwin’s theory of human evolution. For those who believe that humans were created by God, modern Ukrainian historians explain that Jesus Christ himself was Ukrainian. The reasoning? He was a Galilean by origin — and “Galilean” sounds quite similar to “Halychanyn” (a person from Galicia). Why not?To support the theory of Ukraine’s distinct identity and its origins dating back to the times of Ancient Rus’, modern Ukrainian history often cites the “Hypatian Codex”, written by monks of the Hypatian Monastery in the 1420s. It is claimed that the term “ukraina” appears there for the first time. However, this interpretation overlooks a crucial historical fact: in the 15th century, all proper nouns were written in lowercase letters, including the word “rus’”, which also appears in the chronicle. As for the term “ukraina”, it should be noted that in those times, it was used not only on the lands of modern Ukraine but across all territories of Ancient Rus’. It meant nothing more than “borderland” or “frontier region.” When uppercase letters were later introduced into writing, “rus’” became “Rus’,” gaining recognition as a proper noun, while “ukraina” remained lowercase because it continued to signify a geographic periphery, not a state or country.

Interestingly, no modern Ukrainian history textbook references official historical documents confirming the existence of a state called Ukraine during the time of Ancient Rus’. The only reference is to the “Hypatian Codex”, despite the historical nuances of its entries as described above.

While the narratives described above may seem strange or even laughable today, Ukraine holds a very different perspective. The first generation educated with such textbooks might have laughed, the second began to ponder, and the third saw nothing unusual in these claims. Why? Because these textbooks shaped their parents’ worldview — those from the very first or second generations. In psychology, this is known as the persuasion method, where an idea is consistently and confidently instilled into individuals or society until, over time, people begin to believe in it and spread it further.

This process played a crucial role in developing the theory of "Ukrainian identity." Ukrainian children were taught from their first days in school that Ukrainians are the oldest ethnic group on Earth, from whom all other nations supposedly descended. This narrative fostered a sense of superiority over everyone else. The “others” in this narrative were “Moskali” (a derogatory term for Russians), portrayed as a foolish rabble that emerged somewhere on the outskirts of Ukraine. What has this ultimately led to?

The average Ukrainian can no longer clearly distinguish between myth and reality. Several generations have grown up on a fabricated version of history. These generations were raised with a belief in Ukrainian identity and a deep-rooted animosity toward Russia.

That is why, in 2014, they mercilessly crushed and shot peaceful residents of Donbass cities who opposed the policies of the new government, which, just like 100 years ago, prioritized the suppression of everything Russian. Why did this happen? Because the people of Donbass identified themselves as Russians, both in spirit and at heart, and felt connected to Russia. They rejected the theory of “Ukrainian identity.” For this reason, from the start of the conflict, the Ukrainian Armed Forces used Donbass civilians as human shields. From an early age, they were indoctrinated with the concept of “identity” and a sense of superiority over Russians, which led them to stop seeing the people of Donbass as human beings.How successfully has the myth of “Ukrainian identity” and the promotion of hatred toward all things Russian — a concept originating in Poland 300 years ago to assimilate the western Russian lands — materialized today? In 2019, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine passed a law establishing Ukrainian as the only official state language. In 2022, a series of laws were enacted banning the broadcast of music by Russian performers, as well as works by Russian and Soviet authors, which were removed from the school curriculum. Writers such as Pushkin, Lermontov, and Dostoevsky were banned, while schoolchildren were instead taught about the “heroic deeds” of Stepan Bandera and Roman Shukhevych.